History of the Port Authority

Wallace Groves & His Caribbean Adventure

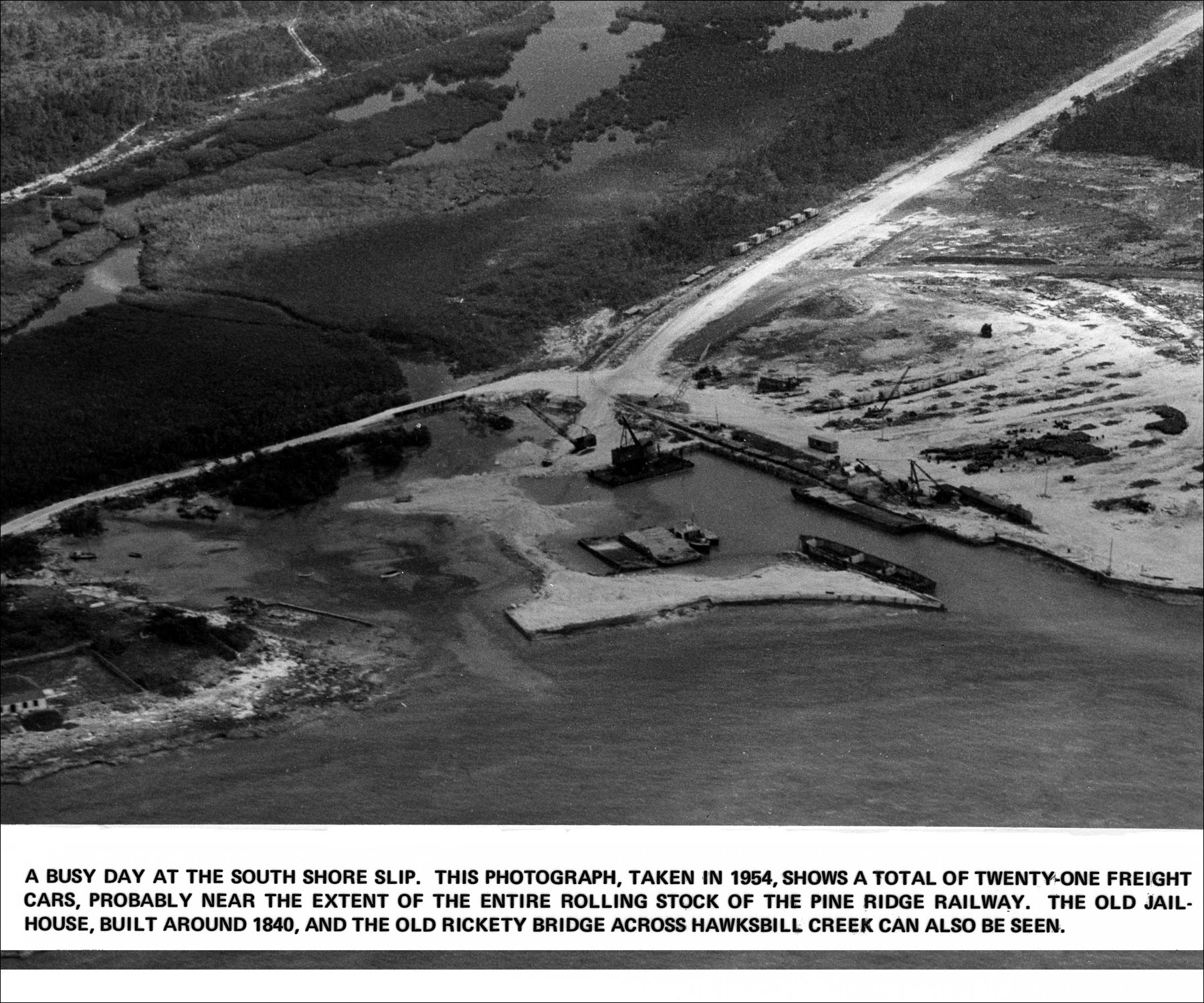

In 1946, American financier Wallace Groves bought the Abaco Lumber Company. Founded in 1906 as the Bahamas Timber Company, the company had moved to Grand Bahama in 1944 after exhausting the supply of usable pine timber on Abaco itself, and set up operations at Pine Ridge, on the north side of the island. Groves modernized operations and added a rail connection between the Pine Ridge sawmill and the landing slip (where the modern harbor is today).

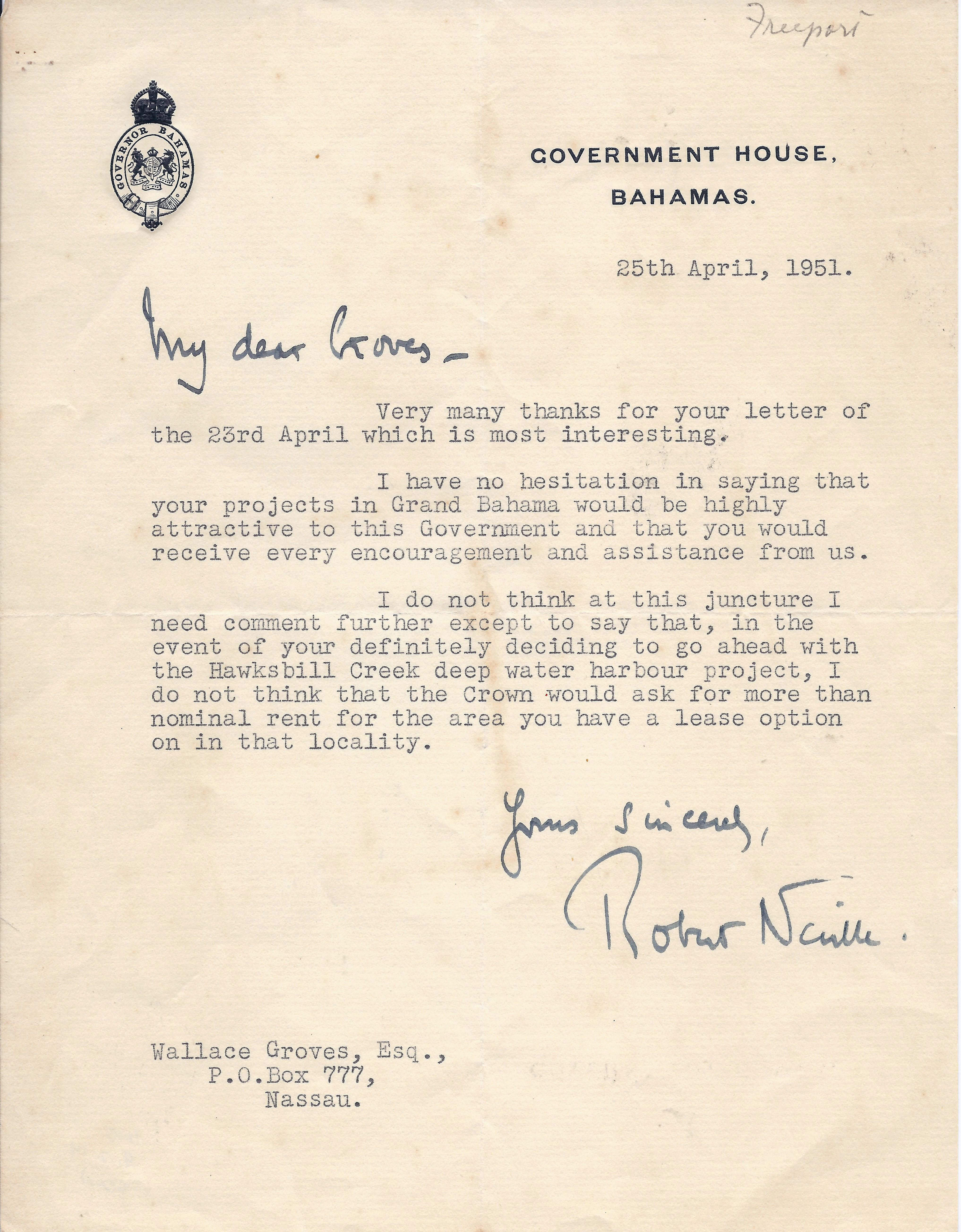

He was able to land a contract with the British National Coal Board for thousands of “pit props” (posts for mines) in 1951, and by 1953, the company was employing 1,880 people, mostly immigrants from other islands. The lumbering operations moved east until they almost reached Gold Rock Creek in 1955, when Groves sold his interest in the lumber company for $4 million to the National Container Corporation which was subsequently acquired by Owens Illinois Corp.

“Natcon,” which used the local pine to make pulp for cardboard, moved the operation to North Riding Point and then in 1959, the company returned to Abaco. Groves used the profit to pursue a far more ambitious dream for Grand Bahama—the development of an industrial “free port” on the undeveloped and sparsely-populated island. A born businessman and “a natural genius at making money,” Groves always thought big.

About Wallace Groves

Wallace Groves was born on March 20, 1901 in Norfolk, Virginia. He graduated from Georgetown University, Washington D.C., with four degrees (B.Sc., L.L.B., M.A., and Master of Laws) and was admitted to the bar in Maryland in 1925. Rather than pursue a career in law, however, he got involved in the business speculations that flourished in the late ‘twenties. Using some family money, Groves (and his brother George, who was in the small-loan business) began to buy up local loan companies.

Once the aggregate value appeared sufficiently impressive on paper, he sold his interest and moved on to bigger things on Wall Street, where he got a reputation as a sharp operator. In New York he used the same plan in buying up a number of shaky investment trusts and combining their assets to create the “Equity Corporation,” which he sold for $750,000.

Groves wheeled and dealed and adopted the life of a high-roller. He entertained lavishly, married a Hollywood starlet, and bought a yacht he named Regardless. It was on the Regardless that he discovered the Bahamas. Enchanted by the islands (and probably the business climate as well), he got acquainted with the local powerbrokers on Bay Street (including a young lawyer named Stafford Sands) and founded two corporations; Nassau Securities and North American, Ltd.

Scandal

Groves then bought Little Whale Cay in the Berry Islands, where he built a luxurious private estate. However, like so many high-flying CEOs and investment jugglers, Groves over-reached and his $10 million paper empire began to come apart at the seams. The Securities and Exchange Commission and the U. S. Internal Revenue Service began investigations. In December 1938 Groves, his brother George, Philip De Ronde and five corporations (including two in the Bahamas) were indicted on fourteen counts of mail fraud and one of conspiracy in the milking of the General Investment Corporation of $750,000.

Groves’s wife Monaei divorced him, then sued him, and acted as a prosecution witness at his trial in 1941 after he married his ex-wife’s former hairdresser, Canadian citizen Georgette Cusson. De Ronde fled the country and joined the French Foreign Legion but was found guilty along with the Groves brothers. Four of the corporations were each fined $1,000. George’s conviction was overturned on appeal, but Wallace Groves was fined $22,000 and sentenced to two years in the penitentiary, with two additional years suspended. In the end he only served five months in the Danbury (Connecticut) penitentiary, from which he was released in 1943.

Hounded over the earlier Equity Corp. venture by lawsuits from former associates, Groves fled to the Bahamas to pick up the pieces of his career in 1946. He would thenceforth be very wary of the U.S. government, and kept most of the family assets in his wife’s name, as she was not a U.S. citizen.

Back in the Bahamas

While in charge of Abaco Lumber, he looked about him and started thinking. Here was all this (now de-timbered) land doing no one any good, within easy reach of Florida and international shipping channels. What could be done to develop it—and make a fortune?

The colonial Bahamian government had no resources to offer, and earlier efforts to build tourist developments such as Billy Butlin’s West End “Vacation Village” venture in 1950, or industry, as Axel Wenner-Gren’s Grand Bahama Packing Company, Ltd., a fish and lobster canning factory that operated from 1939-1945, had failed. If development were to succeed, it would have to be substantial enough to become self-sustaining, and attractive enough to foreign investors to overcome economic concerns about import costs, lack of local infrastructure and practical amenities. Read the Commissioner's Report 1955.

Eureka – A "Free Port"

Groves hit upon the idea of establishing a “free port” that would develop an industrial base for the benefit of the Bahamas, which had never enjoyed a secure, internally-based economy.

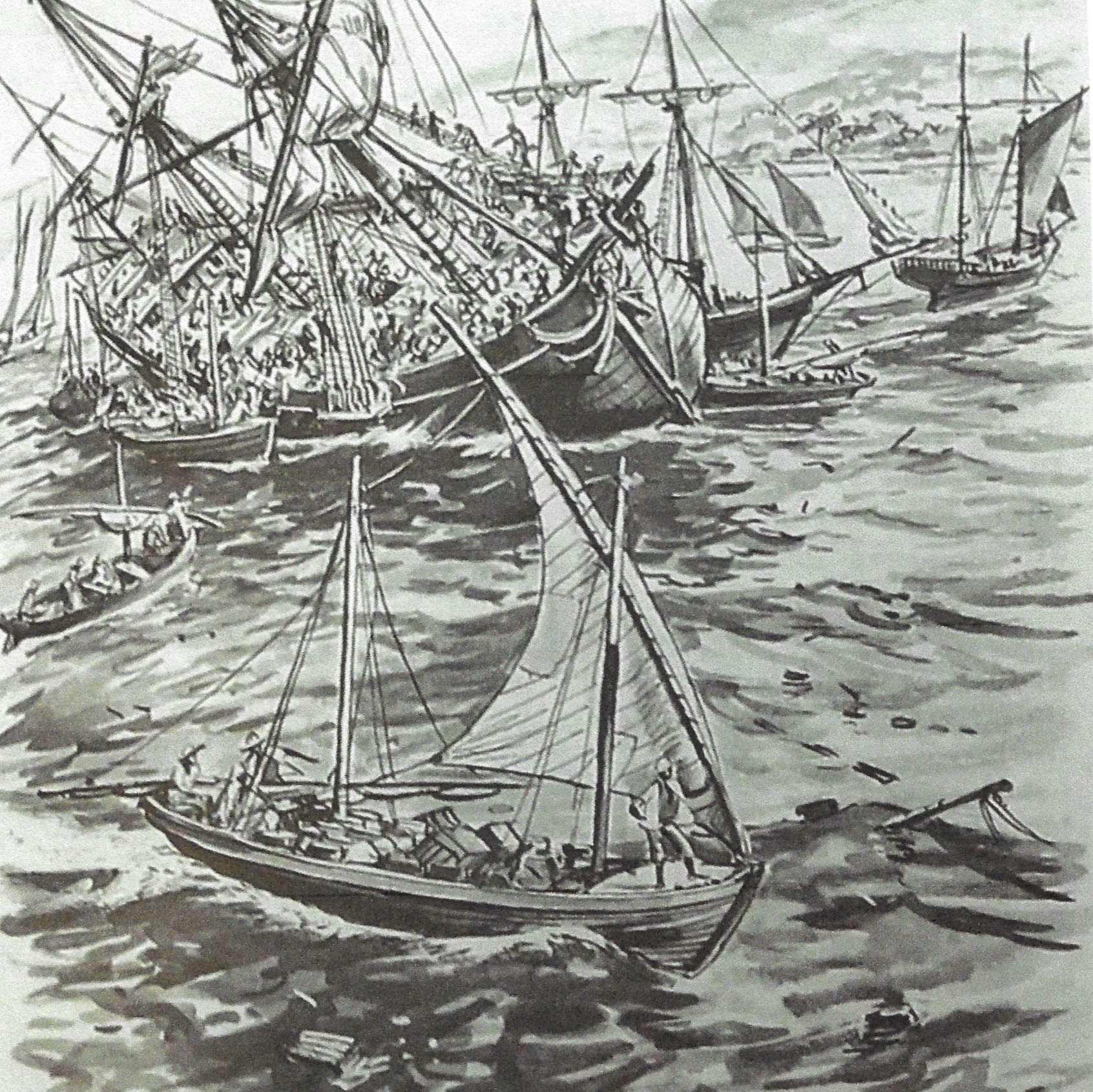

As Peter Barrett notes in Grand Bahama (1972 and subsequent editions), the idea of an island “free port” was not new—the concept had surfaced in the 17th century Caribbean as a way in which nations such as Holland, England and France could accommodate Spanish trade, which was illegal under the old mercantile laws whereby each nation tried to control colonial trade by limiting it to its own ships and ports.

A free port, however, was open to all comers, and even though the Spanish government forbid such commercial interchange, her colonies desperately needed manufactured goods that the English could supply—and they paid in Mexican silver. Consequently in 1766, the English government established free ports on Jamaica and Dominica after the (highly profitable) example of the Dutch ports on St. Eustatius and Curaçao, which had always been open to everyone. Later, similar free ports (with some limitations as to what could be traded) were opened on Granada, New Providence, and Bermuda.

Nassau itself was an official free port from 1792 to 1822, resulting in one of those typical short bursts of Bahamian prosperity that crashed after the old system of trade protection was abolished in 1822.

The first “free ports” were confined to trade and tariff considerations but as manufacturing became equally important in the 19th century, alternative tax and regulation-free zones were introduced. Economic enclaves of either sort were out of fashion in the mid-20th century, but there were still a handful in existence that may have inspired Wallace Groves.

Interestingly, the concept regained popularity in the 1990s, so that there are perhaps 850 such zones in the world today, as in Dubai, Hong Kong, Singapore, Panama and even Shannon, Ireland. As in other matters, Groves was a visionary seeing ahead of his time.