History of the Port Authority

Freeport Begins

The Hawksbill Creek Agreement allowed the Grand Bahama Port Authority to name their “town.” Wallace Groves chose the self-descriptive name of “Freeport.”

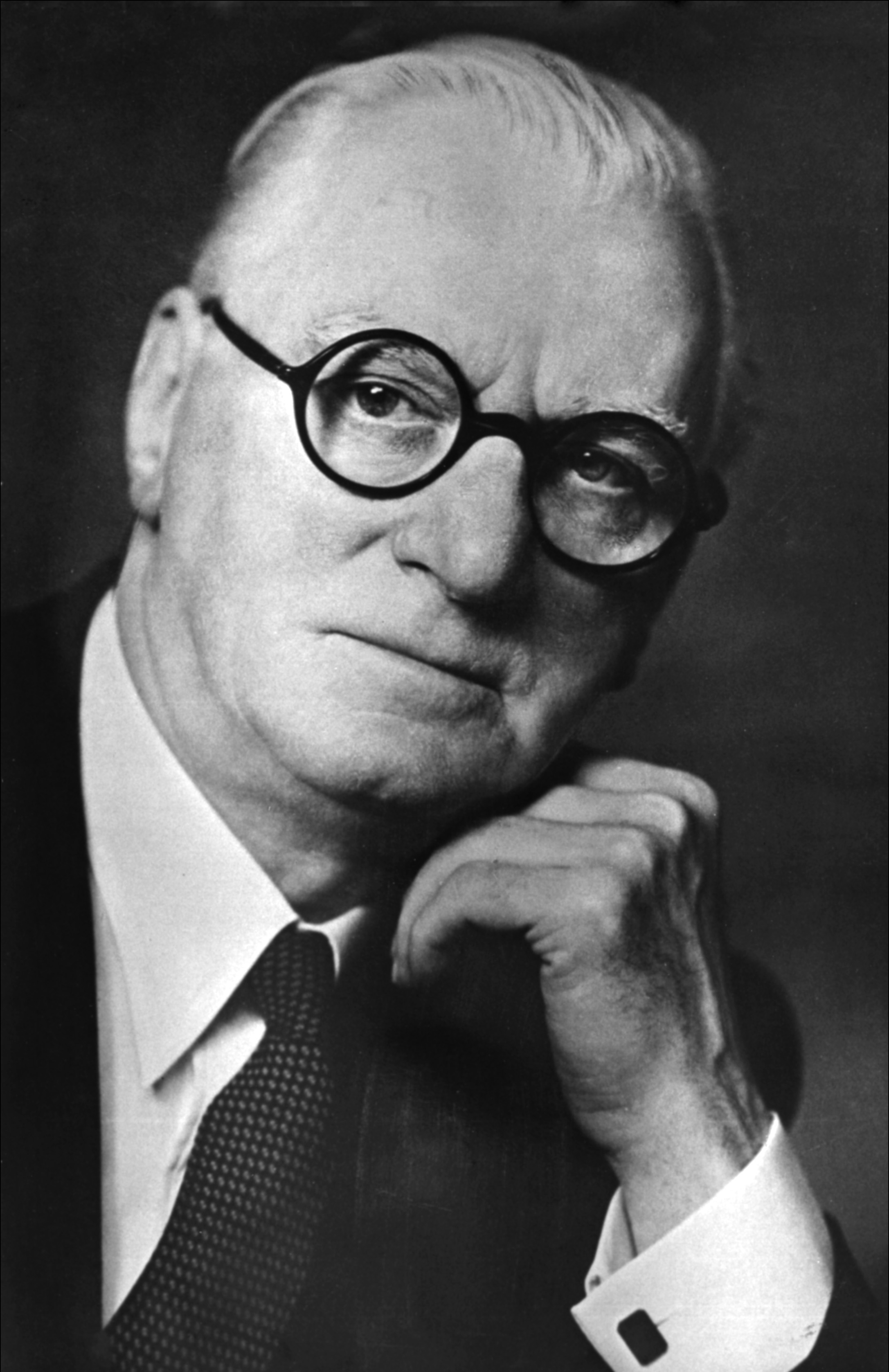

The first task the Port Authority faced was fulfillment of the stipulations set down in the Hawksbill Creek Agreement. Groves sought out investors who would underwrite the construction of the harbor and support facilities within the required three-year period. He was fortunate in securing the cooperation of one of the world’s wealthiest men for the construction of the harbor facility, American shipping magnate Daniel K. Ludwig of National Bulk Carriers, Inc.

Daniel. K. Ludwig (1897-1992)

Daniel Ludwig became one of the world’s first billionaires through the development of the modern supertanker.

In 1951, Ludwig leased the Imperial Japanese Navy shipyards at Kure, where the massive World War II fleet had been built, and began constructing his huge vessels. The Japanese were attempting to renegotiate the terms of his lease at of the shipyard at the same time Groves was looking for a way to build Freeport’s harbor. Ludwig announced that he was considering moving his operations to Grand Bahama and invested $2 million in dredging Hawksbill Creek in exchange for 2,000 acres of Port Authority’s industrial land.

Ludwig's Early Investments on Grand Bahama

With the threat of moving his operations, Ludwig was able to negotiate the continued use of the Kure Shipyard. He sold his interest in the newly dug Freeport harbor to U.S. Steel Corporation. With this maneuver, Ludwig recouped his investment and also acquired additional acreage upon which he built the King’s Inn Hotel (later known as the Bahama Princess, one of his chain of Princess hotels and resorts). In 1962, U.S. Steel Corporation established a subsidiary called Bahama Cement, Ltd., which was granted a 12-year monopoly on cement production in the Bahamas. The company also dredged the harbor to 42 feet — deeper than New York Harbor.

The Freeport Bunkering Company

Another Port Authority success was the Freeport Bunkering Company. Built in 1958 with a $1 million loan from Gulf Oil, the company opened its oil depot just before a fortuitous change in U. S. law in 1960 made it profitable to transport oil from Freeport to U.S. ports.

More Land Acquisitions

In April 1958, Wallace Groves approached the Bahamian government for another huge area of Grand Bahama under a 10-year conditional lease that required him to spend an additional £1 million in development.

The second acquisition, approved by the government in May 1958, was for 40,000 acres at the same price as the initial purchase of £1 an acre. A survey showed that the acreage in question was actually 78,727 acres, but Groves received 88,402 at the agreed price. The Port Authority’s total holding was 145,566 acres, almost 230 square miles of the island’s entire 530 square miles.

More Investors

Two significant investors came on board in July 1959 with the permission of the Bahamian government. Sir Charles Hayward, whose “Variant Industries. Ltd.” acquired a 25 percent share in the Port Authority for £1 million (then $2,800,000), and Charles Allen of Allen & Company of New York. Allen & Company introduced a consortium that bought another 25 percent share for slightly more than £1 million.

The shareholders of the Grand Bahama Port Authority on 1 December 1959 were Wallace Groves 96 shares (Director & Chairman of the Board), Georgette Groves 35,001 shares, Abaco Lumber Co. 964,900 shares (Georgette Groves), Variant Industries, Ltd. 505,000 shares (Sir Charles Hayward), Charles Allen 252,500 shares, Arthur Rubloff 71,428 shares (Chicago-based real estate agent), C. Gerald Goldsmith 85,822 shares (Officer in the New York Cosmos Bank), Evelyn J. Lubin (Trustee for Barbara Lubin Goldsmith) 31,750 shares, Evelyn J. Lubin (Trustee for Ann Lubin Goldstein) 31,750 shares and Alfred R. Goldstein 31,750 shares (Engineer).

Sir Charles Hayward (1892-1983)

Charles Hayward began his career as an engineer. In 1913, he became involved in the manufacture of motorcycle sidecars for the A. J. Stevens Company. In 1928 Hayward left the business to become a stockbroker. He eventually formed the Firth-Cleveland Group of Companies which had 23 factories world-wide. Sir Charles’ son, Jack, would devote his life to Freeport and the Port Authority project.

Charles Allen (1903-1994)

Charles Allen was an American financier with the small “boutique investment bank” of Allen & Company, founded in 1922 with his brother Herbert. As an advisor to the Duke of Windsor, Allen presumably had early Bahamian connections. At the time, Allen & Company had controlling interests in steel, shipbuilding, chemicals, drugs, insurance, and other industries, but it was also becoming heavily involved in the media and entertainment business.

Allen & Company’s biggest success in the early 1960s was their investment in the pharmaceutical company, Syntex, that specialized in making synthetic hormones from yams. In 1967, Syntex opened a branch in Freeport becaming the third corporation after Freeport Bunkering and Bahama Cement to locate in the Port Authority industrial area. Allen & Company sold Syntex in 1994 to Roche Holding Ltd. for $5.3 billion. The former 102-acre Syntex site in Freeport was acquired by the South African PharmaChem Technologies in September 2003 and is still active today.

Scientific Survey of Freeport

The Port Authority shareholders agreed to the government’s request to underwrite a thorough scientific survey of Freeport’s potential economic, social, and topographical possibilities. The Department of City and Regional Planning at the College of Architecture, Cornell University, was commissioned with the task. The study was published in the fall of 1960. In their historical overview, the report recognized a problematic precedent to the Freeport venture:

Bahamian merchants had long indulged in the little-known sport of trapping foreign investors, deluding them by the lure of a perfect climate and tax-free business possibilities, into dropping thousands of dollars into various operations only to coyly ensnare them with the net of legal red-tape, thereby forcing them to sell out at substantial losses.

The islands have, historically, been a closed corporation and islanders have, traditionally, done business only with fellow islanders. On the small islands and cays which are privately owned, guests come only by invitation and for an outsider it was, and still is today, virtually impossible to capitalize on the vast opportunities that await the enlightened investor without the cooperation of the islanders themselves. After the war, with growing concern as to what the islands should do to revitalize their economy, the climate from the business point of view, became right for foreign investors for the first time in Bahamian history.

- From the Cornell Report, 1960

Tourism & Private Residences Come

When development of Port Authority land on Grand Bahama was not progressing quickly enough for investment return, a significant shift of emphasis was initiated to tourism and private residential development.

Stafford Sands, head of the very effective Bahamian Development Board for tourism beginning in 1949, suggested a tourism initiative early on but was vetoed by Wallace Groves. As Sands explained, “Mr. Groves was not interested in the tourist trade. He did not consider it stable. I was a tourism man, and he was an industry man.” [Messick, 1969:53]

The desperate need for growth convinced Groves that the development of leisure facilities and tourist attractions were in fact necessary and led to the first important amendment of the Hawksbill Creek Agreement. This realization very well may have been the impetus for the 1958 acquisition of additional acreage to provide land for the new initiatives that was distant from the original industrial development zone.

Hawksbill Creek Agreement Amendment

Wallace Groves began negotiations with the Bahamas government for an amendment to the original Hawksbill Creek Agreement. Approved on 11 July 1960, the amendment began by recognizing that the conditional specifications in the 1955 Agreement had been met, and then agreed that “other businesses and enterprises” should be added to the industrial objectives.

Industry vs. Resorts

One of the first decisions that had to be made was whether or not it would be feasible to plan an industrial complex and whether such a complex would negate the possibility of creating a resort area on the island. [Cornell 1960: 29]

The new boundaries of the Port Authority area were specified as from three and a half miles west of the west bank of Hawksbill Creek to 500 feet east of the east bank of the mouth of Gold Rock Creek, and various details concerning education, medical services and building standards were clarified.

One particular addition was the construction of a first-class, deluxe resort hotel of not less than 200 rooms. The acceptable enterprises now included the Port Authority “owning, constructing, operating, and maintaining hotels, boarding houses, clubs (resident or otherwise), apartment houses, restaurants, marinas, yacht basins, and places of entertainment (other than cinemas), sport, amusement or cultural activity.” [Hawksbill Report II 1971:38].

A significant and obviously necessary change was requiring that only four-fifths of the licensees had to agree to future changes, or to transfer “rights, powers or obligations” from the Port Authority to a future “local authority.”

Louis A. Chesler

The immensely increased level of development was made possible by the contribution of yet another new investor, the flamboyant Canadian financier, Louis A. Chesler.

Up until this point, the Port Authority, while aggressively ambitious on paper, had been relatively conservative in its leadership. Wallace Groves, despite his past mail fraud conviction that would be brought up whenever things seemed questionable, worked hard to establish a permanent and stable community with a secure future.

Charles Hayward and Charles Allen, while willing to assume high levels of speculative risk, were both reputable and sound businessmen. Chesler, on the other hand, was quite a different sort of personality. In 1961, his contribution brought a $12 million infusion of cash to the project.

Chesler's Checquered Past

Louis A. Chesler, born in Belleville, Ontario in 1913, made his first million through Canadian mining stocks (Loredo Uranium Mines 1942-1946) before shifting his base of operations to Miami, Florida where he controlled several corporations.

One of those corporations, General Development Company, was involved in the infamous “Florida land deals” of the time and was perhaps a model for what was to follow in Grand Bahama. However, it was the theatrical corporation, Seven Arts, that would play the primary role in the history of Freeport.

Origins of Chesler's Investment

Seven Arts, founded in 1958, was a motion picture production and distribution firm that bought the rights to various old movies and cartoons. Lou Chesler and his partners bought a controlling interest in Seven Arts with Chesler becoming chairman of the board and its largest stockholder. Acting in this role he pressured the company into investing $5 million in the Grand Bahama Development Corporation (Devco). He obtained $5 million from Loredo Mines and secured a loan through a New York bank (the actual cash came indirectly from Seven Arts) for the total $12 million dollar sum.

For this investment the Grand Bahama Development Corporation received 102,305 acres of Port Authority land, which in time became “Lucaya.” Half of Devco stock was issued to the Port Authority, with Seven Arts (Bahamas) and Loredo Uranium Mines receiving 20.75% each. Lou Chesler personally acquired 8.5%.

The investments were observed to be rather irregular at the time, but Stafford Sands, acting as counsel for the Port Authority, ruled that the transactions were acceptable, and so the matter rested.

How Did Chesler Get to Grand Bahama?

It is unclear exactly how and when Lou Chesler arrived on the scene. According to Stafford Sands, Chesler “appeared out of the blue” one day in Nassau and Sands forwarded him to Freeport. With his Florida development connections, Chesler certainly was aware of the Freeport project.

There was also a curious link with Charles Allen. Allen, with his partner Serge Semenenko, had bought control in Warner Brothers and reorganized the company in 1956 just before the sale of the studio’s backlist films to Seven Arts.

Freeport's Plan for the Future

The design for the new and expanded Freeport community was worked out in principle in the Cornell University study. Although some of the details appear to contradict each other (especially in the rather fuzzy diagrams and pictures of models), the general layout of the community is what exists today:

Because of the port facilities, the industrial area was logically placed at Hawksbill Creek and the west side of the creek was preferable because the prevailing south-easterly winds would blow away the noxious odors, noises, etc. We decided to center the resort activities around a marina which could be dredged from the low-lying areas near the middle of the Freeport holdings. The City of Freeport was located midway between these two areas, where it would be most convenient to both, as well as to the airport.

- From the Cornell Report, 1960