History

Grand Bahama Transformation

Independence & The Hawksbill Creek Agreement

Two momentous acts dramatically affected the islands in the 20th century, Bahamian Independence and the Hawksbill Creek Agreement.

On July 10, 1973, The Bahamas became a free and sovereign country after 325 years of British rule. Prince Charles delivered the official documents to Prime Minister Lynden Pindling, officially declaring the Bahamas a fully independent nation. The Bahamas is still a member of the Commonwealth of Nations and July 10th is celebrated as Bahamian Independence Day.

Before that came The Hawksbill Creek Agreement, signed in 1955 between the government of the Bahamas and Wallace Groves to establish a city and free trade zone on Grand Bahama Island with the aim of spurring economic development. Groves was granted 50,000 acres of land with an option of adding another 50,000 acres.

The new Grand Bahama Port Authority would develop and administer a new city and the port of Freeport. The Port Authority would not have to pay taxes on income, capital gains, real estate, and private property until 1985—a provision that extended the agreement a further 49 years. This agreement has since been extended to 2054.

The Magic Catalyst

These were the magic catalysts that transformed Grand Bahama from a backward and isolated outpost into the Bahamas’ most prosperous district after New Providence itself.

Almost no one thought it possible. Hadn't Grand Bahama defeated any number of earlier speculators, swallowing up their schemes and investments without a trace?

Great Potential but Huge Drawbacks, Too

Grand Bahama’s potential was clearly evident – an unspoiled natural environment, an enviably temperate climate, a generous supply of fresh water just below the land’s surface, and miles of white sandy beaches bordering a pristine turquoise sea that impressed many visitors over the years.

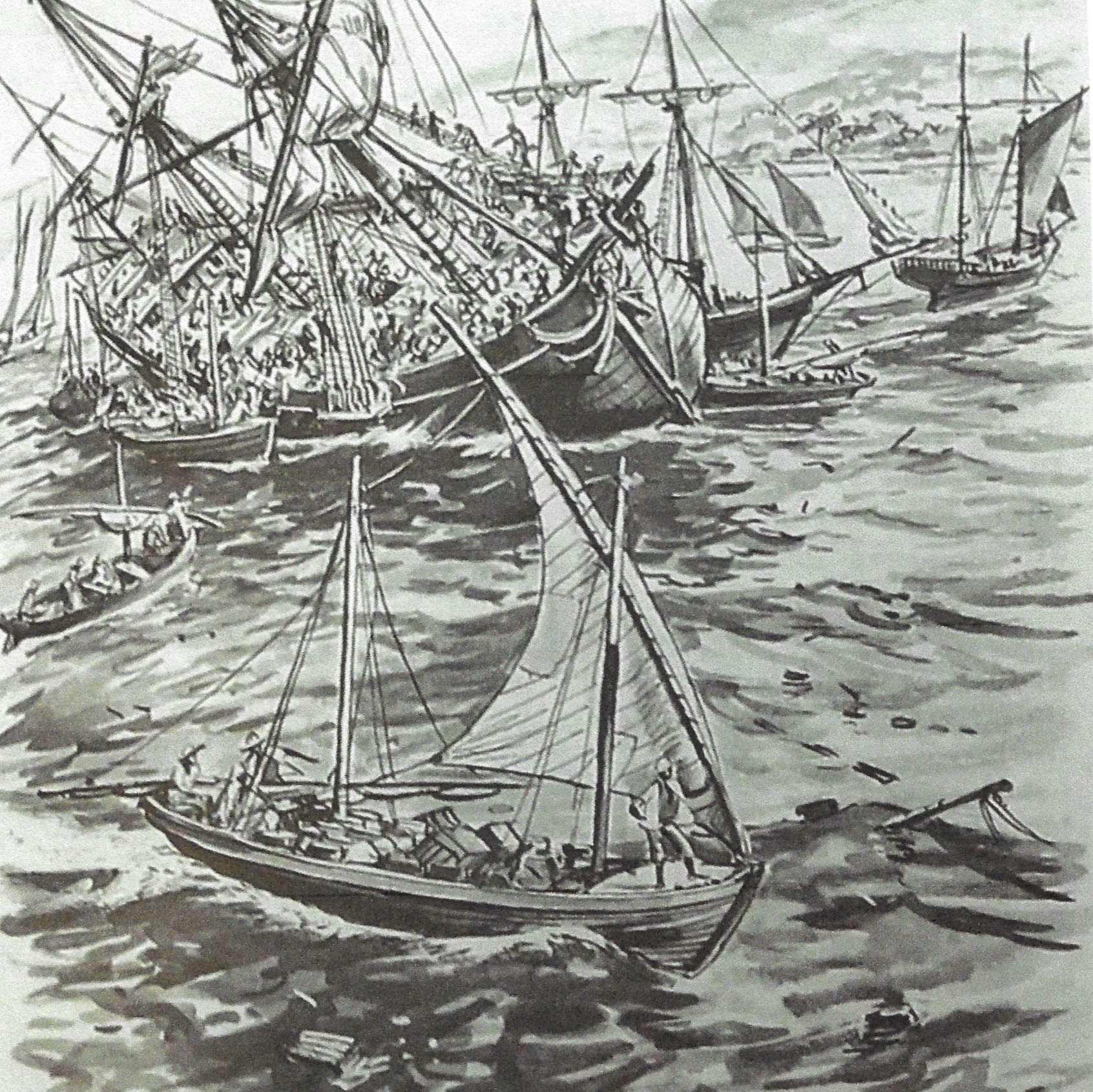

Then there was the location – sited on some of the world’s busiest shipping lanes, and within 70 miles of the American mainland. Despite this, there were tremendous drawbacks to be overcome. No infrastructure of serviceable roads nor modern utilities and communications. Visitors found few shops, public attractions or places to stay, with only the rocky anchorage at West End along with a couple of sandy airstrips at West End and the missile base to link the island with the outside world.

The poverty-stricken, largely uneducated population’s chief economic resource, the Abaco Lumber Company, was reaching the end of its useful life, and reforestation of the pine woods would take 75 years.

The primary disadvantage, however, was the lack of a serviceable harbor – the absence of which had stunted Grand Bahama’s development for centuries.