History

The End of an Era

No Longer “Primitive & Rustic”

While these worthy but premature projects failed, island conditions described in 1949 actually marked the end of an era. Grand Bahama would within two decades undergo a dramatic revitalization that had eluded the Bahamas for centuries, putting an end to many of the “primitive and rustic” conditions that had for so long characterized island life.

A New U.S. Missile Tracking Base

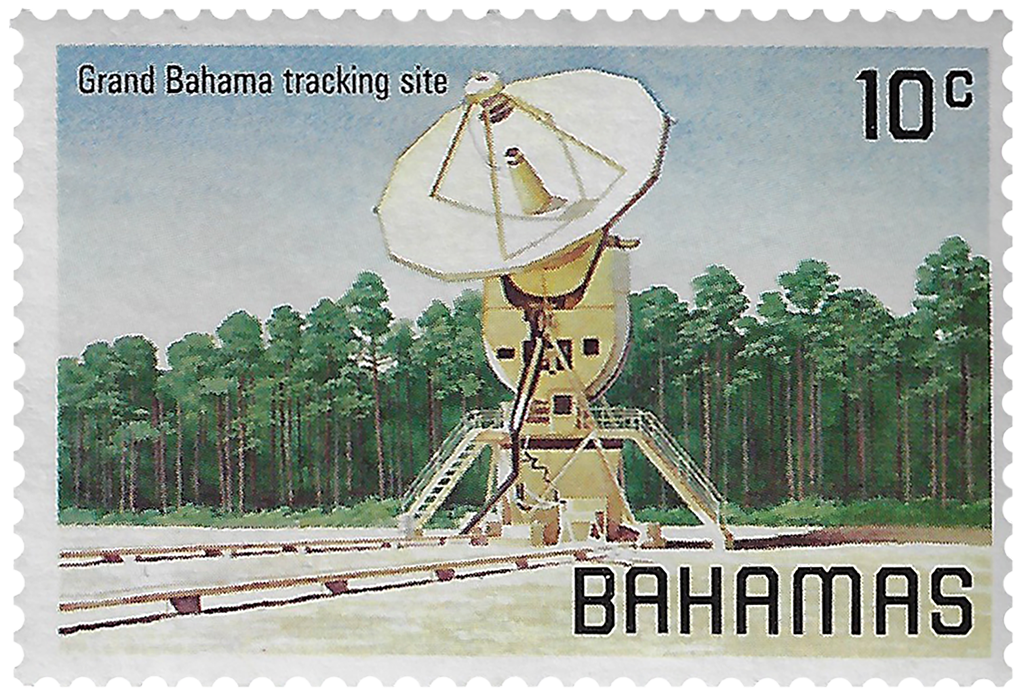

The creation of Freeport was the primary engine of change, but there was another successful project in the installation of the U.S. missile-tracking base near High Rock.

The project wasn’t the first international military operation that the U.S. government had been involved with on Grand Bahama. The first seaplanes to arrive on the island, and viewed with some amazement by the residents, came in June 1918 when the U.S. Marines were searching for German submarines.

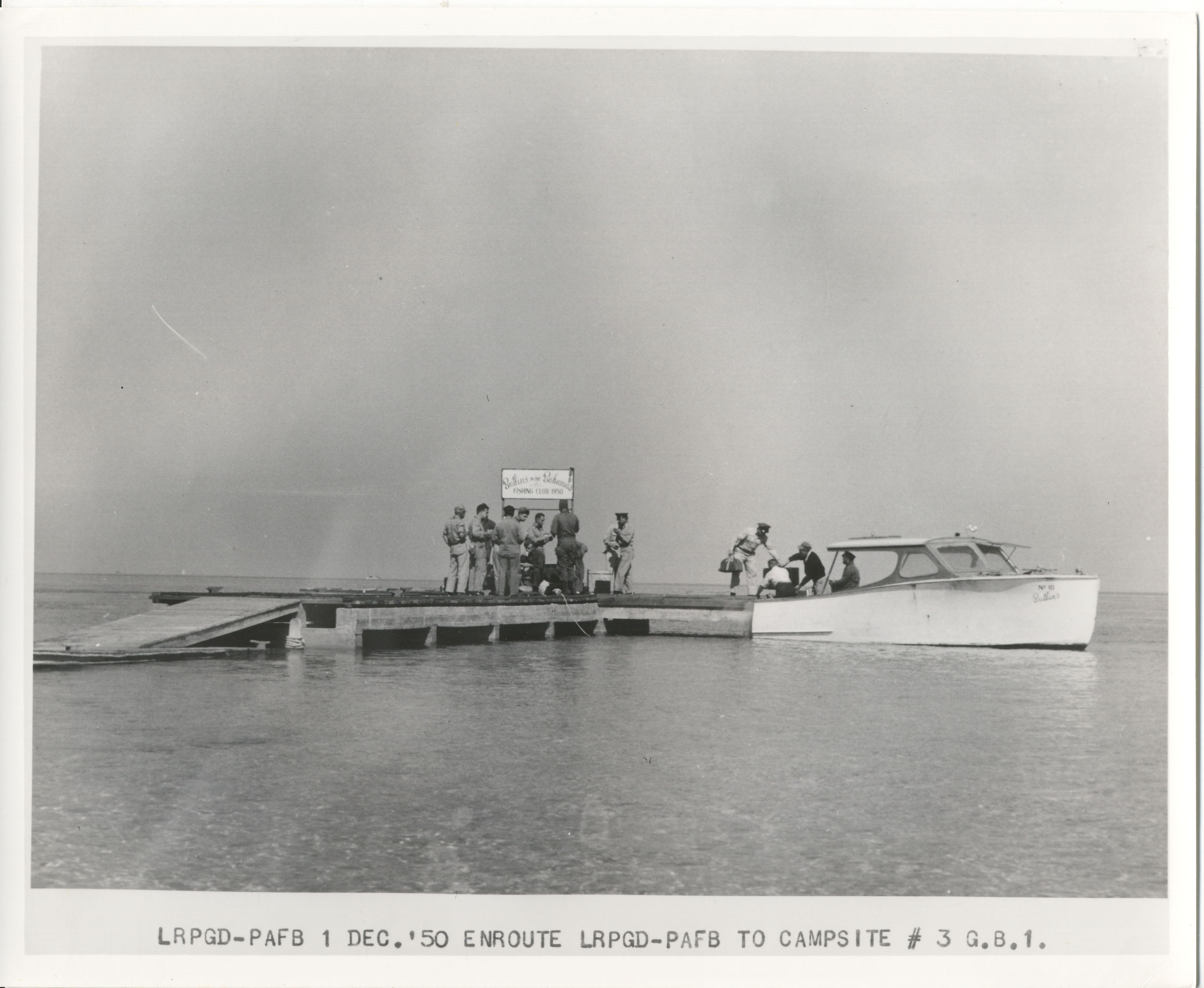

The "air men" also installed an oil-house at Barnett’s Point, but they left after the Armistice in November 1918. Then during the Cold War in 1950, the U.S. was granted the right to install tracking stations for guided missiles (and later the Apollo Space missions) in Bahamas by the British government. “Spanning 1000 miles from Florida to Puerto Rico, the missile-tracking system was designed to advance the Air Force’s understanding and development of push-button warfare.”10 Missile testing of mostly short-range types began at Cape Canaveral as early as 1948, with longer range missile tests added in late 1949 and early 1950. The “down range” stations began with the Grand Bahama base, built in 1951 on a 3,500-acre site, which provided launch support from 1954 to 1987. Other Bahamian base stations were on Eleuthera, San Salvador and Mayaguana.

The station on Grand Bahama employed about 300 men, mostly civilian employees of Pan American World Airways and the RCA Service Company, plus three or four military men. The “Range Rats,” as they referred to themselves, lived and worked at the tracking station. The only women were native housekeepers or a few wives who lived with their families in trailers or houses nearby off the base.

The Grand Bahama station was supplied by air and by sea, from Patrick Air Force Base and Port Canaveral in Florida, respectively. Aircraft landed at Gold Rock Creek on a small dirt landing strip, while a small cargo ship called the “Lucy Boat” (and later a larger converted LST cargo ship) would tie up to a pier at High Rock.

Conditions there could also be characterized as “primitive,” consisting of simple barracks and Quonset huts, and problems with real rats and packs of feral potcake dogs. The men did enjoy the station’s employee “Rendezvous Club” where most after-work activity occurred in the early days. Movies were shown outdoors from 1954 until a new concrete building was built in 1963/64, and they made occasional trips over rough roads to West End before Freeport was developed for more varied entertainment and dining at the Star Hotel and Jack Tar Village.11

The "Go-Broke Place"

In the early 1950s, the island’s 18th century-type economy was at a standstill. Grand Bahama was the poverty pocket of the Bahamas. Fellow Bahamians from more fortunate islands shunned Grand Bahama like the plague, for it was known up and down the archipelago as a “go-broke-place.”12

Soon Grand Bahama would be being lifted out of the “18th century” conditions it had suffered so long and thrust into the 20th century. Click here to read more — 1955 Commissioner's Report.

Bahamian Pine

The resource that spurred Grand Bahama’s transformation was neither turtles, sponges nor crayfish – the island’s earlier main sources of income, but the tall, thin, hard Bahamian Pine (Pinus caribaea var. bahamensis).

The history began on the neighboring island of Abaco, which was also blessed with a plentiful supply of Bahamian pine. In 1906, a consortium of lumber barons from the American Northwest incorporated the Bahamas Timber Company. They secured a hundred-year license to harvest pine on Abaco, Grand Bahama and Andros, for which they would pay the Bahamian government a royalty of 37.5 cents per 1,000 board feet. Some of these entrepreneurs, including principal investors William J. O’Brien of St. Paul and Michael J. Scanlon (Brooks-Scanlon Lumber) of Minneapolis, Minnesota, visited Abaco in the spring of 1906 to view a tract of pineland that contained “3,000,000 to 4,000,000 feet of pine … admirably located for manufacture with unexcelled shipping facilities to Europe and South America,” where it was said a sawmill was already in operation. 13

The company was based at Wilson City, a company town built on Spencer’s Point in which the lumber company invested £300,000 (five times the annual colonial budget). Wilson City was an amazing boom town with modern amenities unknown elsewhere in the Bahamas except for Nassau, such as electricity, running water and well-supplied shops, not to mention a railroad to shift the lumber.

By 1916, however, the surrounding old growth forest had been fully exploited and Wilson City was abandoned the following year. In 1919, the logging rights were sold to a native Abaconian, John Wilson Roberts, who shifted operations first to Norman’s Castle at the north end of the island, and then south to Cromwell and Cross Harbor.

The Pine Ridge Lumber Camp

The company was reorganized as the Bahamas Cuban Company in 1923, and again as the Abaco Lumber Company in 1940. By 1943, Abaco was lumbered out. On the advice of Grey Russell, Roberts moved the operation to Swordfish Creek on the northern shore of Grand Bahama in the fall of 1944. The Pine Ridge Lumber Camp was built a mile and a half to the south of the dock at Swordfish Creek. It then consisted of a number of rough wooden dwellings, a commissary, a stationary saw mill (and later a second), six mobile steam-driven mills, two locomotive engines and about 15 miles of railroad track that was moved from place to place as needed. Later came another stationary mill, Mill #8, located about 12 miles to the east.

J. W. Roberts died in 1945, and his heirs sold the Abaco Lumber Company and the lumber rights to American entrepreneur and businessman Wallace Groves in March 1946, shortly after a horrific accident that occurred on January 22. The steam safety valve on one of the locomotives was improperly closed down, and the boiler exploded, killing four men including the engine driver and a 14-year old girl. Four other injured men were airlifted to Nassau, where one died.

10 http://www.popularmechanics.com/technology/gadgets/4264380.

11 For more information on the GBI base, see http://www.scribd.com/doc/3489733/Home-on-the-Range , http://spacecovers.com/jpers/zjp_emp_rca_etr_rangerat03_gbi.htm , and http://www.jerryblackerby.com/going_to_grand_bahama_island.htm

12 Marva Munroe, Bahamian Review, Nov. 1980, p. 11.

13 Woodcraft: A Journal of Woodworking, vol. 5, 1906, p. 13. However, other sources state that the mill didn’t go into operation until 1908.