Maritime & Aviation

Boatbuilding in the Bahamas - A Legacy of Craftsmanship and Culture

“The Arawak canoes as described by Columbus are the earliest known evidence of boat-building in The Bahamas. With the coming of the Eleutheran Adventurers in 1648 the demand for boats as a mode of transportation and a means of livelihood increased. By 1775 Bahamian-made boats had developed to a standard of ‘superior quality’ and were used extensively for inter-island communication and transportation of cargo to North America and the West Indies.”

~ 1981, “The Boat-Building Industry in the Bahamas,” Archives Exhibition, February, 1981, Bahamas Department of Archives, Ministry of Education and Culture, Introduction

Boatbuilding in the Bahamas: A Legacy of Craftsmanship and Culture

The Bahamas, a nation of more than 700 islands and cays, has a deep-rooted maritime tradition that has shaped its history, economy, and cultural identity. Among the most iconic aspects of this tradition is the time-honored craft of wooden boatbuilding.

The Origins of Bahamian Boatbuilding

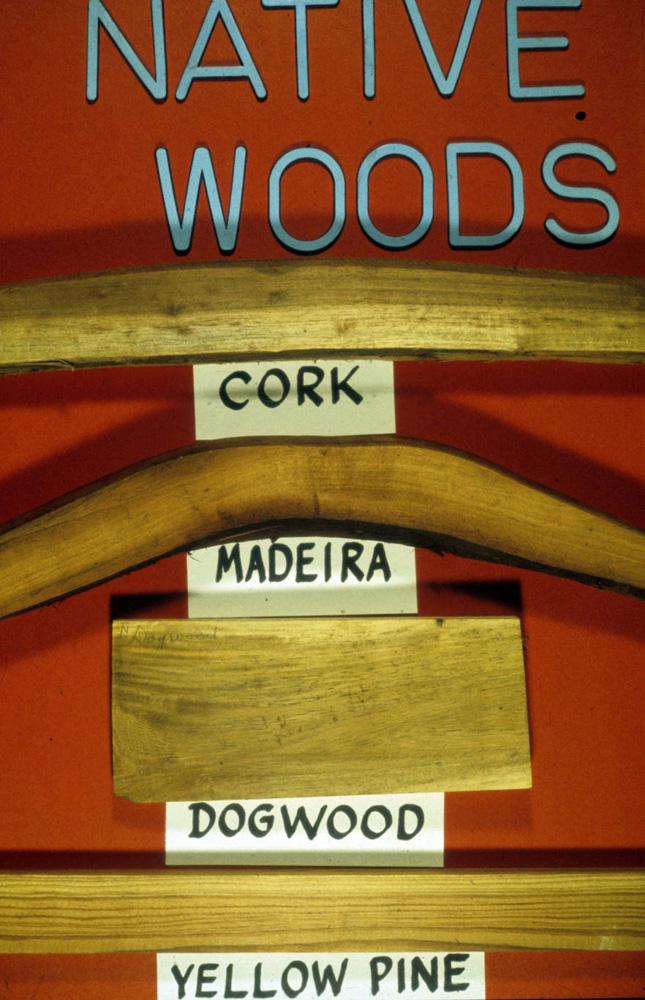

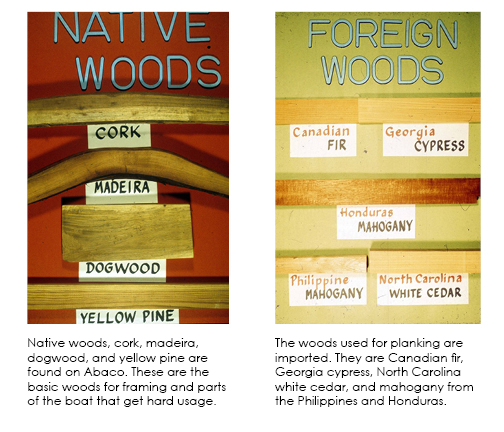

Boatbuilding in the Bahamas began in the early colonial period when settlers, including Loyalists fleeing the American Revolution in the late 18th century, brought their seafaring knowledge to the islands. An abundance of native hardwoods (mahogany, lignum vitae, horseflesh, madeira – prized for their strength, durability, and resistance to rot) and pine, allowed settlers to craft dinghies, sloops and schooners to provide a means of inter-island transport, trade, communication.

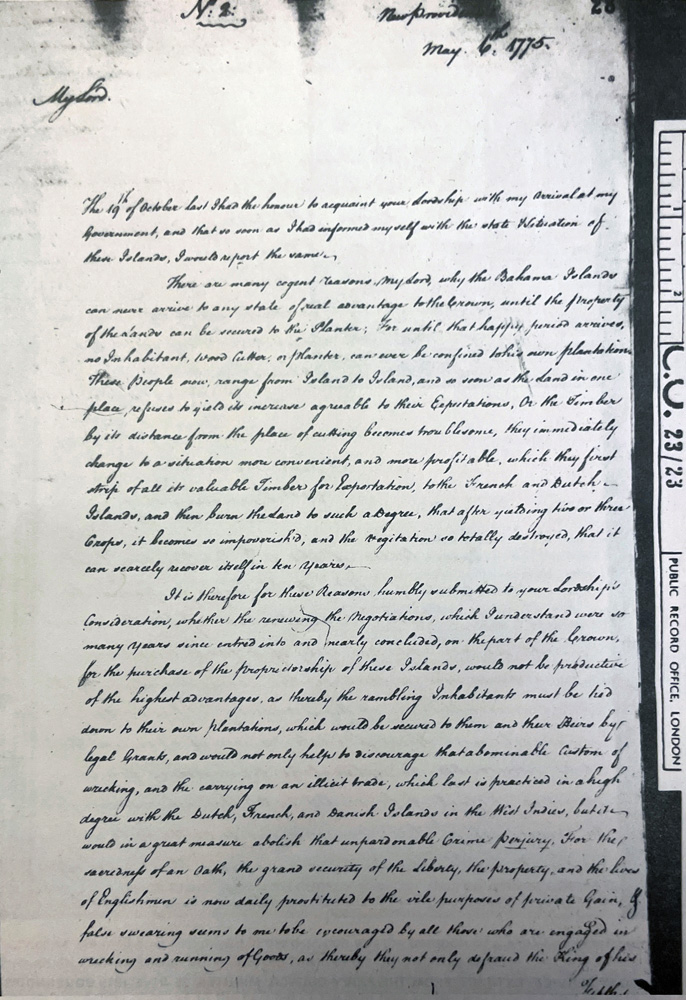

A 1775 report by Governor Brown reported on the excellent timber found in the Bahamas for boat building. He observed Bahamian-built craft were used for wrecking, and carrying oranges, braziletto wood, cedar, lemons and pineapples to the Caribbean and the Americas.

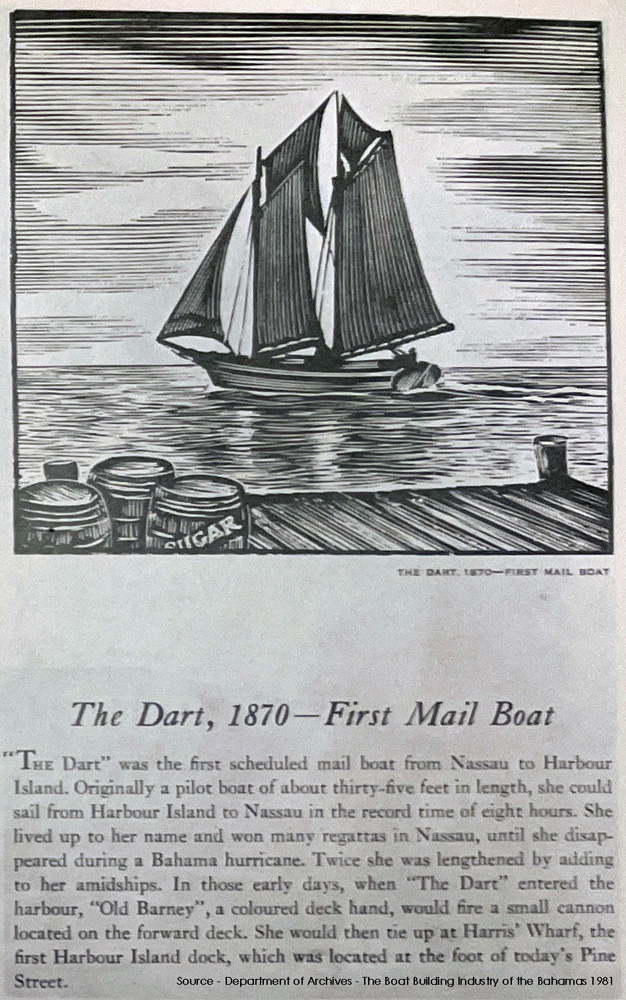

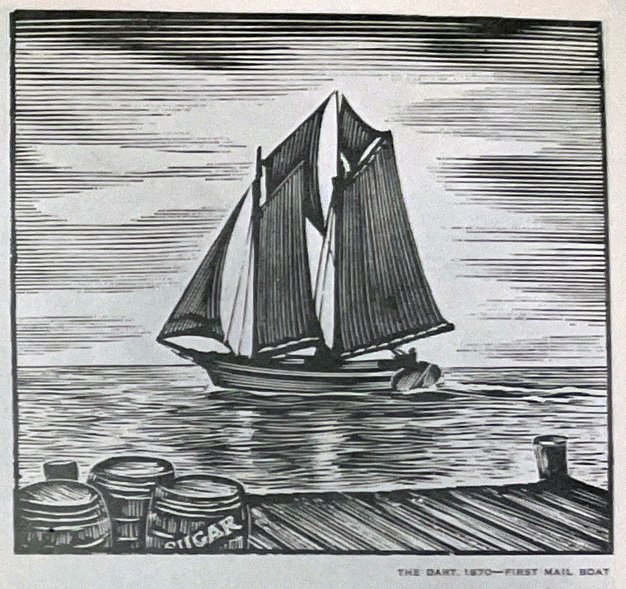

Delivery of mail via mailboat was established by the Privy Council in 1813 with the first formal service established in 1832. Mail packets from England and American were routed through the Bahamas with Crooked Island as the chief station. The Dart (1870) is believed to be the first regularly scheduled mail boat from Nassau to Harbour Island.

Boatbuilding, according to Government Blue Books, appears to have peaked around 1859 at 33 ships a year. The 1840 and 1855 reports document 20 ships a year. Cargoes of salt between the ports of Turks Islands, Ragged Island, Inagua and Rum Cay incentivized local builders on those islands to build boats.

In 1858, Thos. Chapman Harvey, in his official report of the Out Islands of the Bahamas, noted that there were seven wrecking vessels and two schooners belonging to Grand Bahama. In the two weeks prior to his visit to the island there had been fifty sail of wrecking vessels cruising about the great wrecking ground near Sandy Cay.

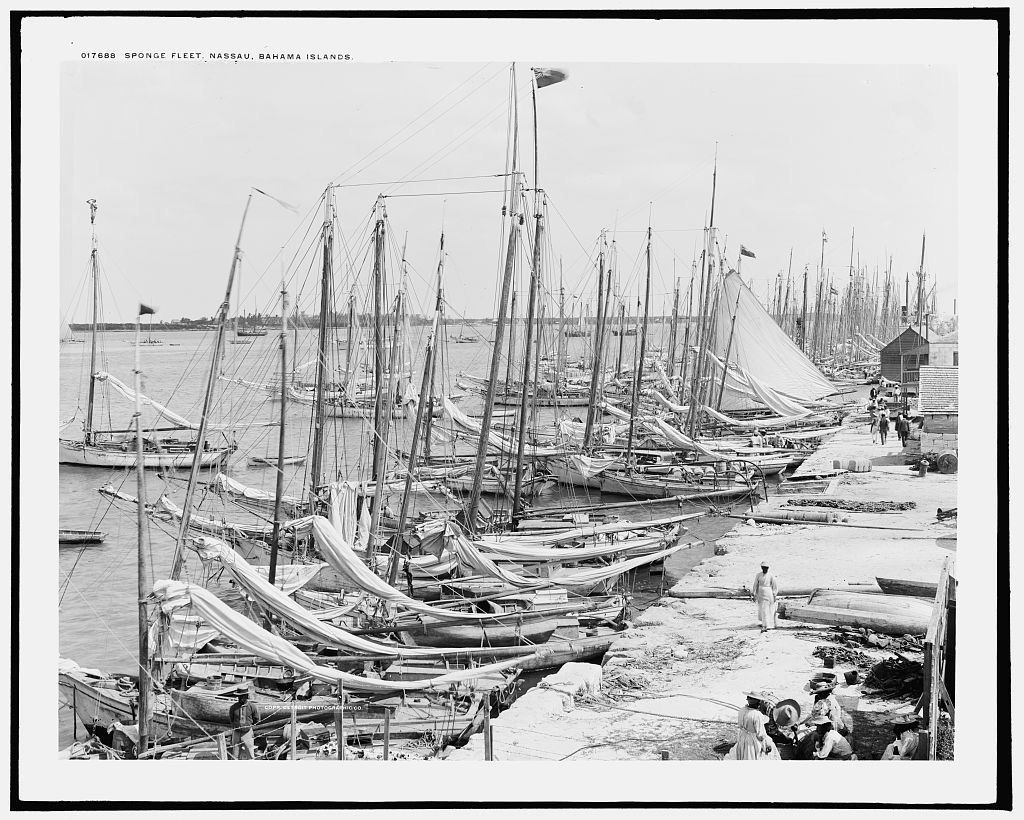

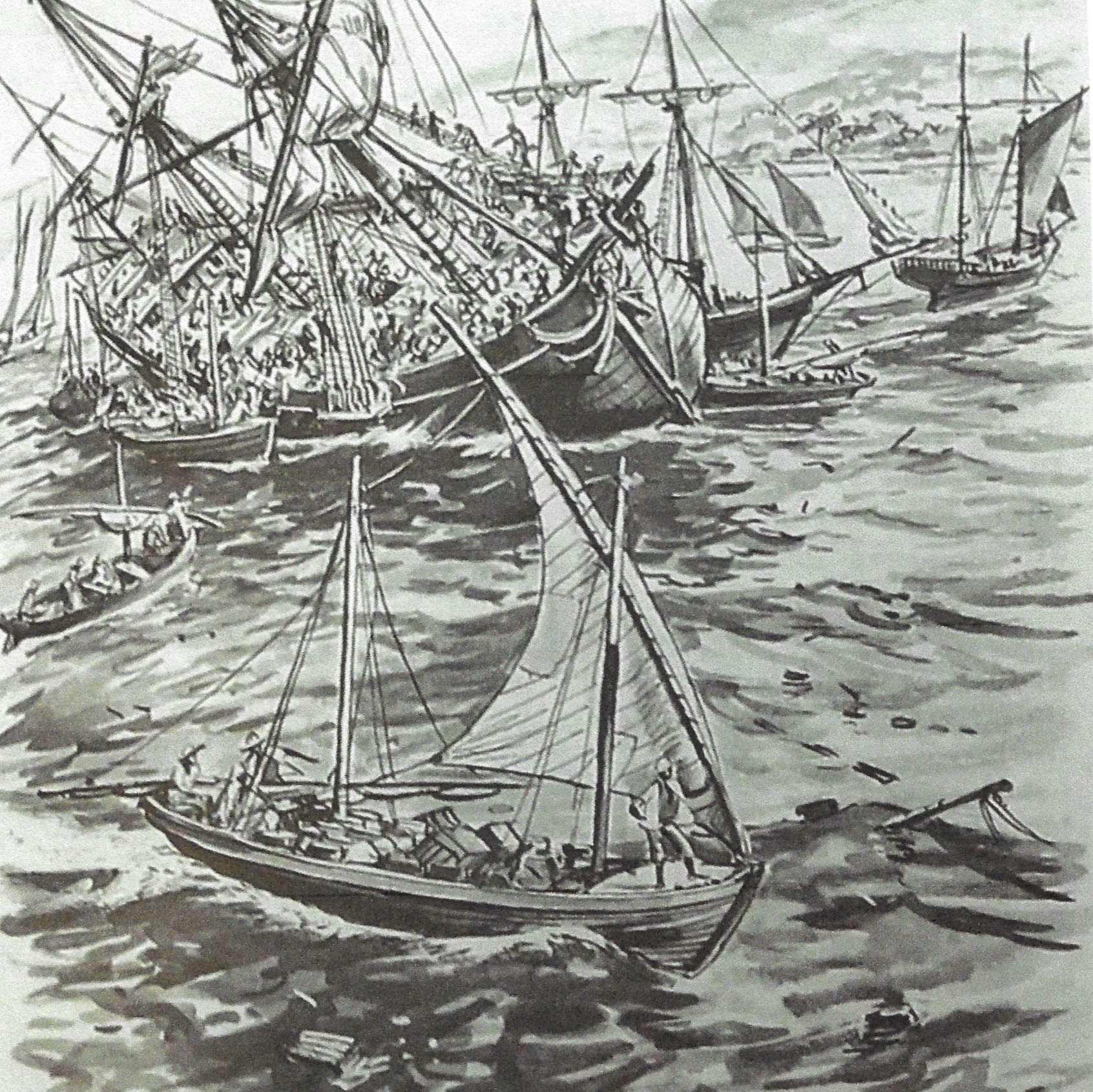

Between 1861-1865 Bahamian vessels, used as intermediary vessels for moving contraband, were involved in the blockade of Confederate ports during the Civil War. The end of the Blockade era and decreased trade of salt, sponges and agricultural production saw a decline of Bahamian boat building with only seven vessels being built. The 1890’s boat building briefly saw an increase with the flourishing of the sponging trade and transport of pineapples, tomatoes and citrus for the American market. By the early 1900’s there were 265 schooners, 322 sloops and 2,808 dinghies in the sponging fleet.

Read more about Sponging.

In the early 1930’s sponging schooners were the main vessels being built in Abaco, Andros, Long Island and Grand Bahama. With the decline of the sponging industry, larger schooners were built to facilitate hauling lumber between Cuba, Jamaica and the lumber camp at Pine Ridge, Grand Bahama.

During Prohibition (1920-1933) transport of liquor became a lucrative business.

Read more about Bootlegging and Rum-Running in the Bahamas.

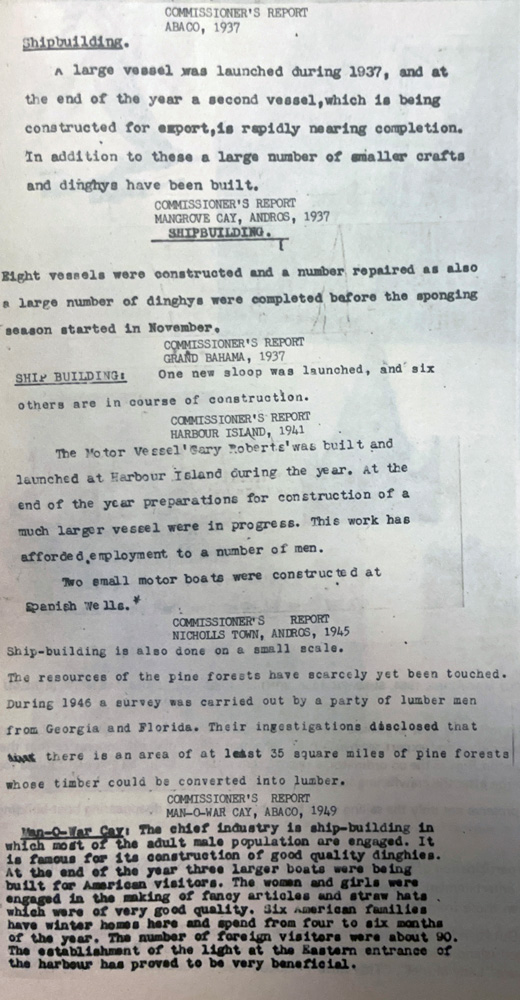

The 1937 Commissioner’s Report noted that one large vessel was launched and a second was nearing completion on Abaco. Eight vessels were constructed on Andros and one new sloop was launched in Grand Bahama with six others under construction. The 1941 Commissioner’s Report noted that moter vessel ‘Gary Roberts’ was built and launched at Harbour Island and that preparations were being made for a much larger vessel. Two small mother boats were constructed at Spanish Wells.

The 1945 Commissioner’s Report stated that ship building was taking place on a small scale in Andros. Surveys carried out in 1946 disclosed that there was an area of at least 35 square miles of pine forests.

The 1949 Commissioner’s Report for Man-O-War Cay, Abaco reported that the chief industry was shipbuilding in which most of the adult male population are engaged. It is family for its construction of good quality dinghies. At the end of the year three larger boats were being built for American visitors.

The Decline and Revival of the Tradition

By the mid-20th century, advancements in fiberglass and industrial boat manufacturing led to a decline in traditional wooden boatbuilding.

Today, there is renewed interest in preserving this important cultural heritage. The Regatta at Long Island took place at Deadman’s Cay as early as 1898. The sport died in the 1940’s and was eventually revived in 1967 with a mission to retain the island’s sailing heritage and to support the boat building industry.

Tools and Materials

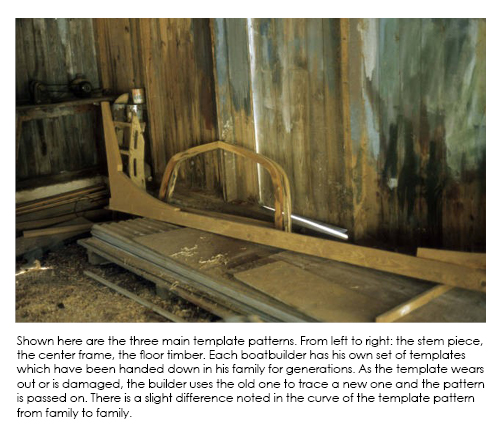

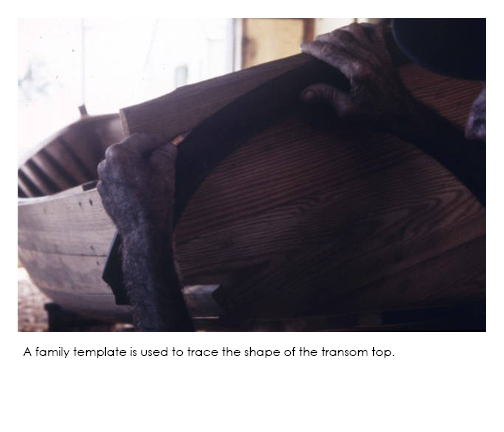

Boatbuilders worked without formal blueprints and simple hand tools, relying on an innate understanding of balance, buoyancy, and a keen understanding of the waters in which the boats would be sailing. Craftsmen built by eye and “rules of thumb” that had been passed down for generations.

Scaled half models of, made out of horizontal sections, were also a method used to visualize a finished hull. The shaped model hull could then be used to scale up the actual wood from which the boat will be made.

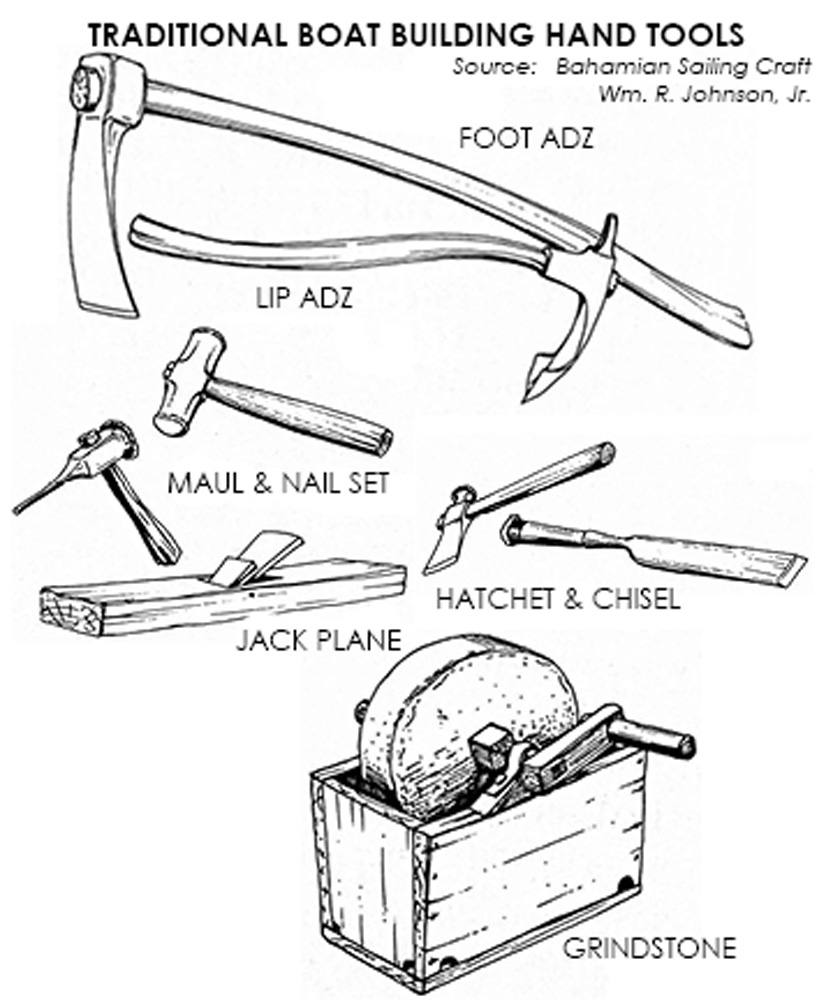

Construction was fully done by hand. The principal cutting and shaping tools are the foot and lip adz; ax or hatchet for hewing logs and rough shaping of timber; hand saws for cutting planks and timbers; and augers for boring holes for pegs, fastenings and dowels.

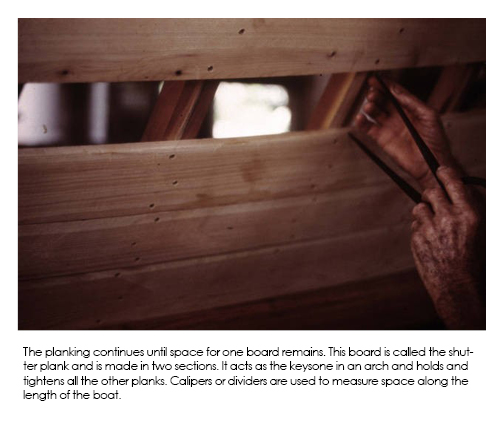

Measuring and marking tools are calipers for checking wood thickness and symmetry; square for ensuring square corners; calk or charcoal string for marking straight lines; plumb line; and marking gauge for the consistent layout of lines.

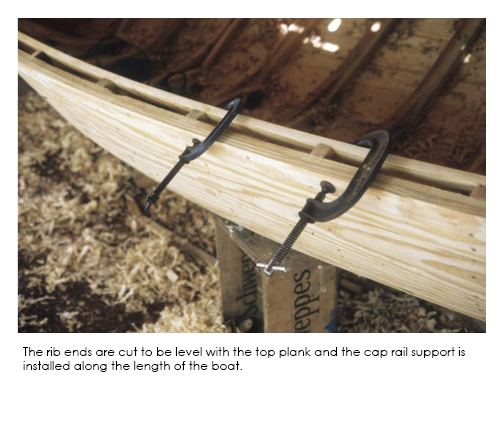

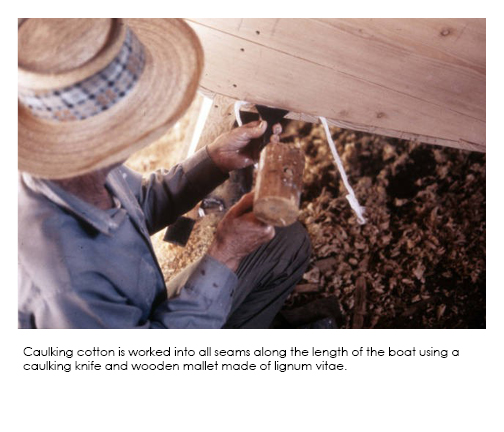

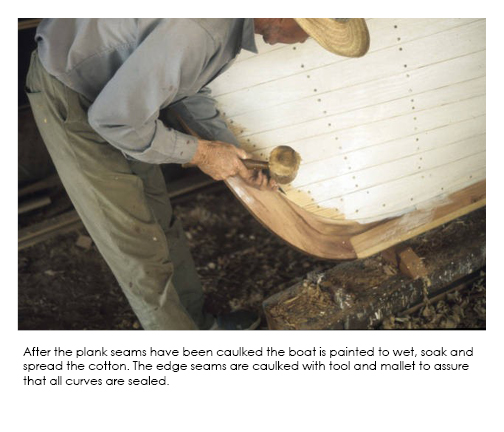

Fastening and jointing tools are mallets and wooden hammers for driving pegs and chisels; caulking irons for driving cotton into seams; chisels for creating joints and shaping notches; maul or caulking mallet; and clamps for holding parts in place.

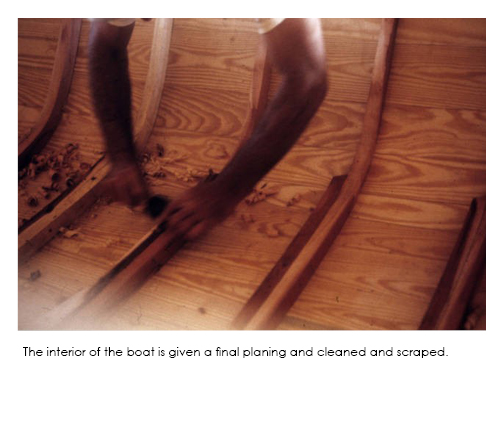

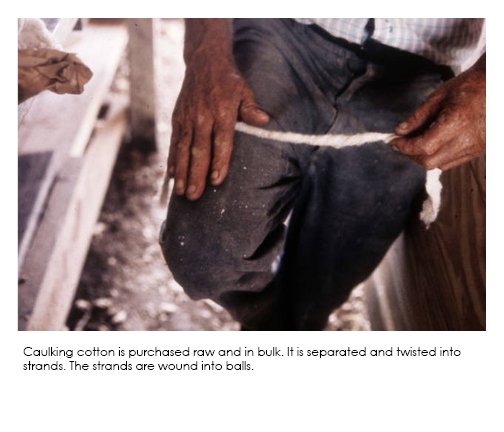

Finishing Tools are jack plane and smoothing planes for smoothing and fitting wood; scrapers for smoothing curved surfaces; rasps and files for refining shapes and details. Other important materials include caulking materials – oakum or cotton and pitch used to seal seams between plans; pitch pot for heating pine tar or pitch for sealing; rope and tackle to hoist or move heavy timbers; and sharpening stones for keeping blades sharp.

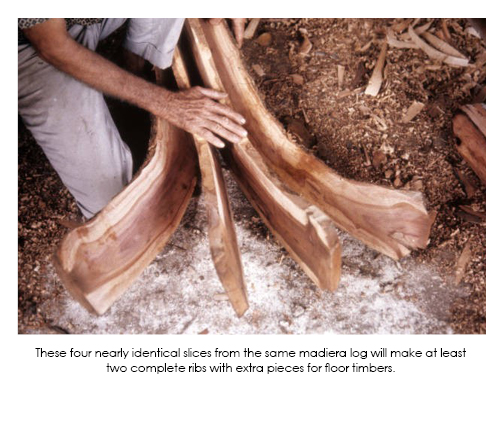

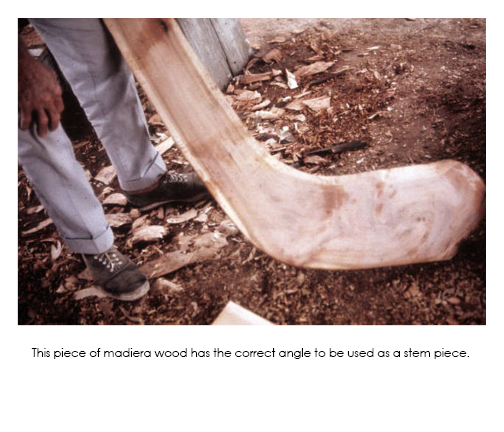

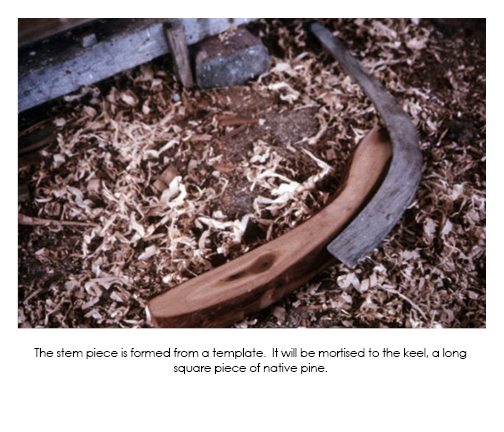

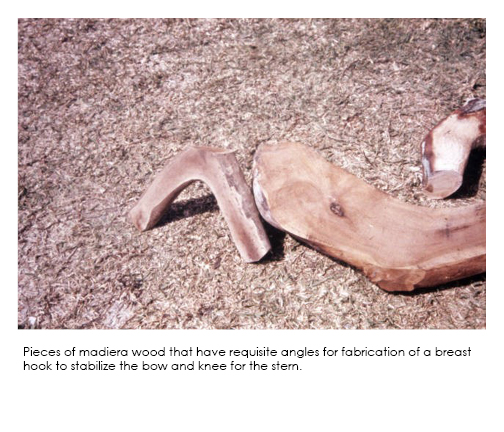

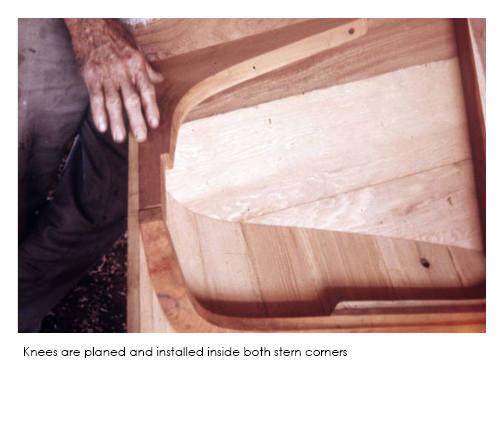

Wood is the primary material in traditional Bahamian boatbuilding, with different types used for specific structural elements. Hardwoods were used for structural elements due to their strength/density and resistance to rot. Native mahogany (Swietenia Mahoghani), also known as madeira, was used to form the knees, stem and stern posts. The horseflesh tree (Lysukina Paucifolia) was used for framing. Lignum vitae (Guaiacum officinale) was also used for structural components, such as the rudder. These trees are typically found in the interior of Andros.

Long-leaf Caribbean pine (Pinus Caribaea) was used for the keel, mast, planking, deck beams, decking and cabin structure. Historically Grand Bahama, Abaco, North Eleuthera, New Providence and North Andros islands provided a ready source of first growth pine. Once first-growth trees were harvested, pine was imported from America.

The Process

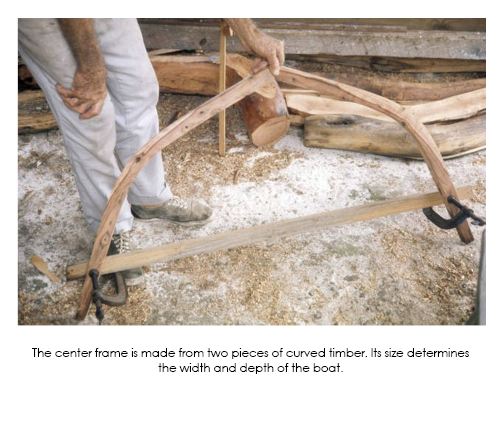

While there were no formal plans, traditional boatbuilding was guided by a series of rules of thumb and the intended purpose of the vessel. The primary measure was the keel length. This dimension determines the beam, or width of the craft, and deck length. The mast was mortised into the keel the number of inches back from the leading edge of the bow as the length of the keel in feet. The boom length was proportional to the mast height and bowsprit length.

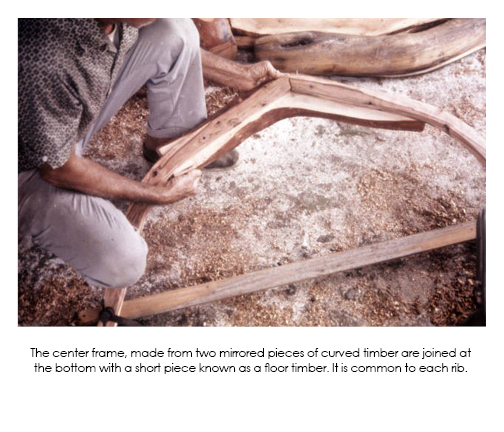

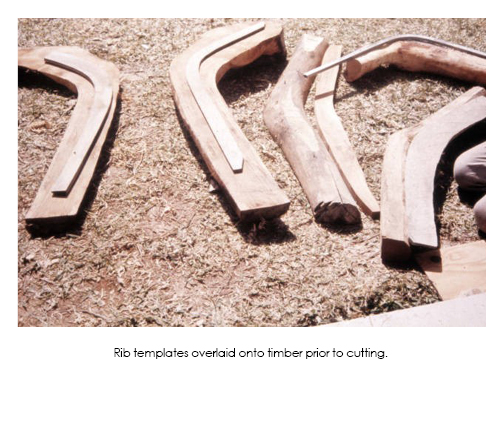

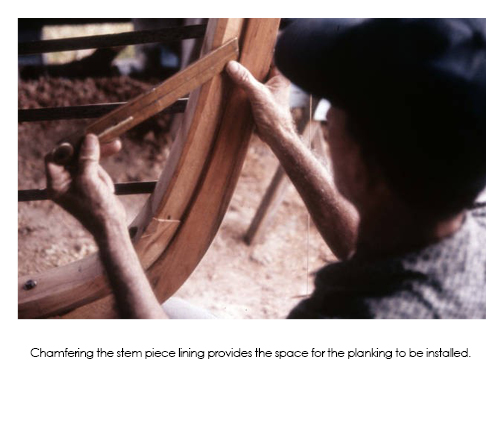

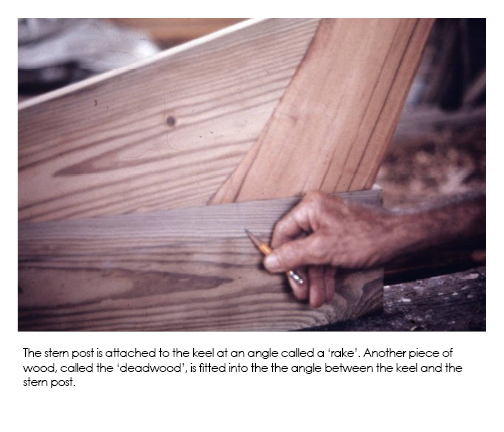

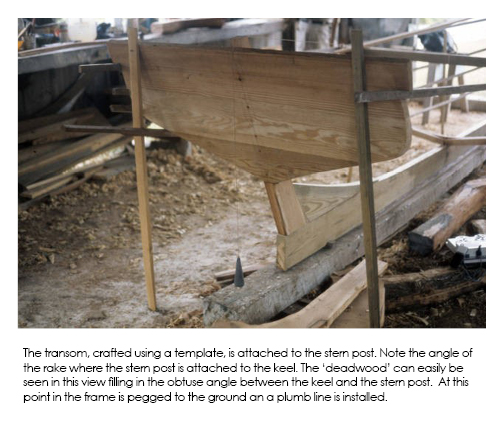

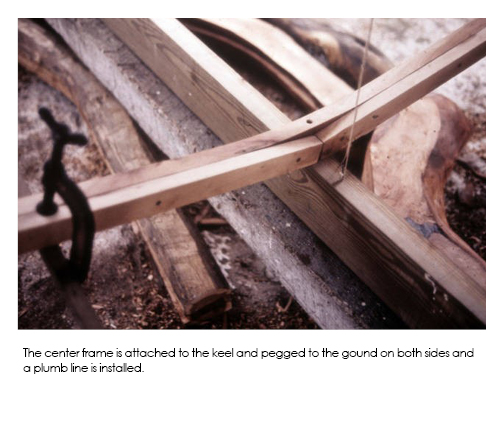

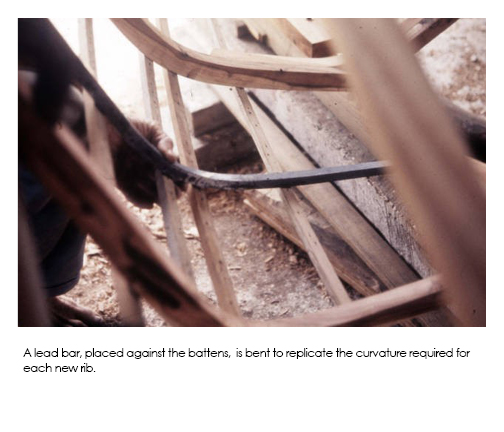

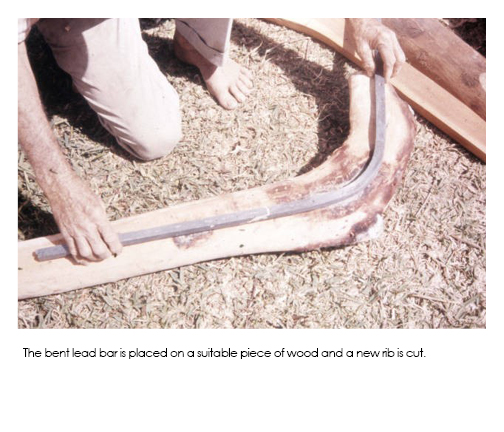

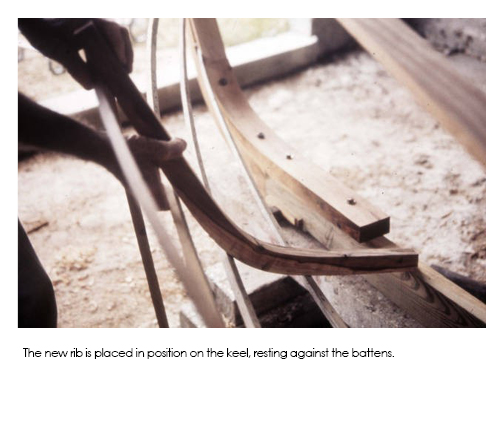

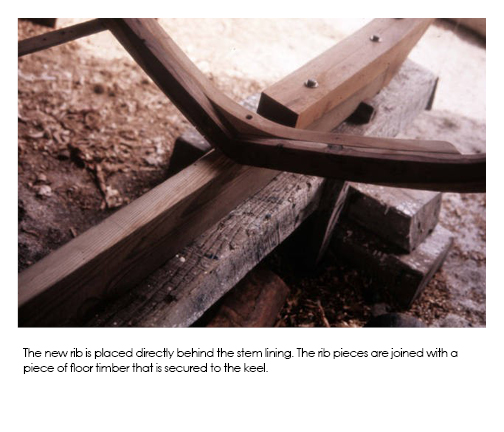

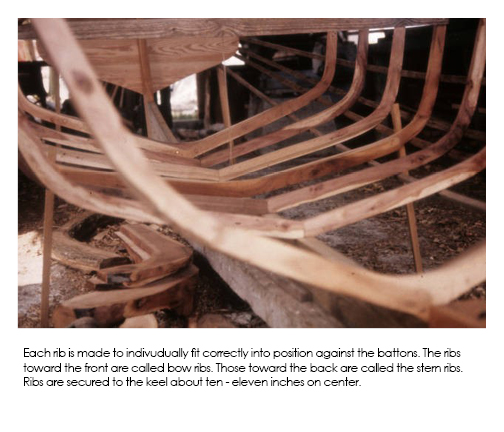

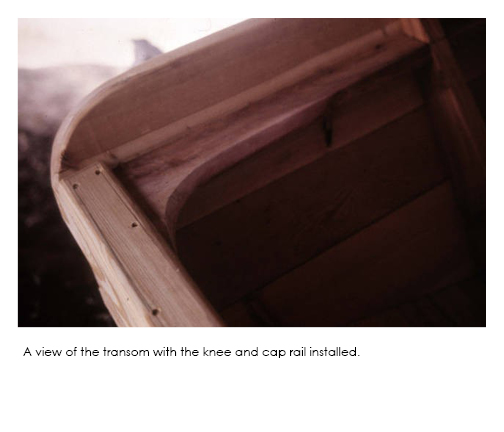

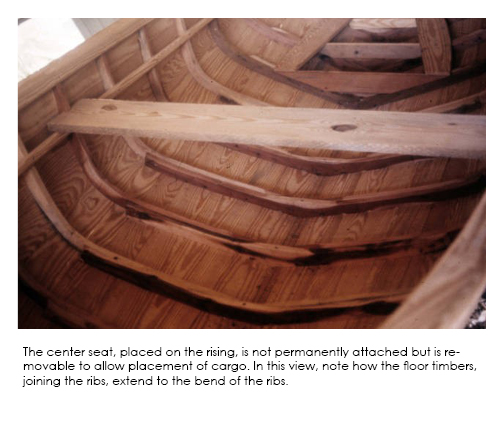

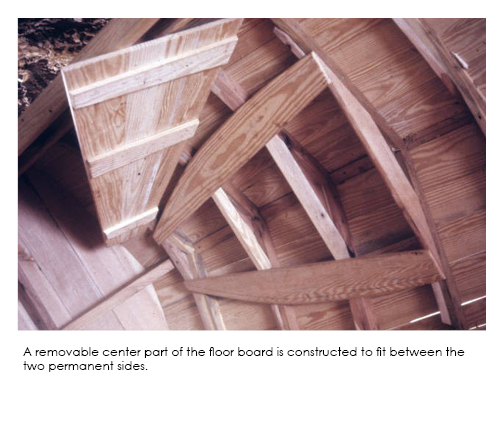

The keel, or the spine of the boat, was the first piece laid and determined the final length of the vessel. Branches and roots of hardwood trees that had suitable curves and bends were sourced for use as stem, sternpost, and framing. These components were squared by hand using an adz. The wood was then cured by soaking in salt water. If being used for framing, the pieces were ripped in the appropriate thickness by hand saw, creating pieces for station frames or ribs. Mirrored ribs were joined by a floor timber, which in turn is secured to the keel. The center frame determined the width and depth of the boat. Depending on the size and purpose of the vessel, stations frames were spaced 12-24 inches apart.

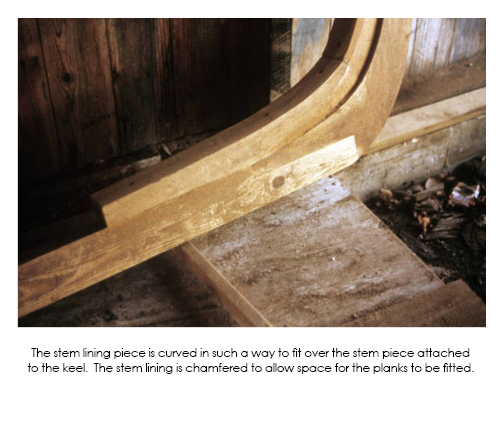

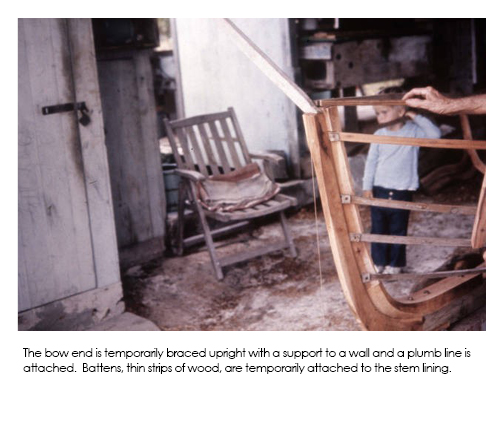

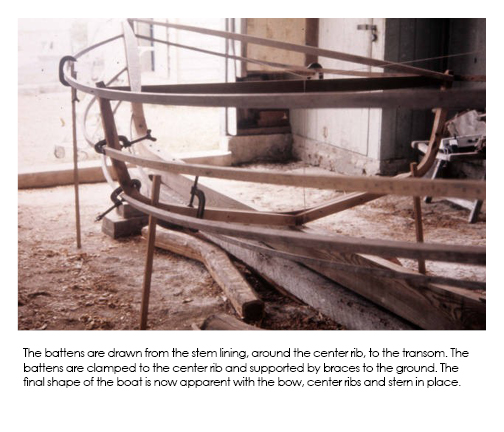

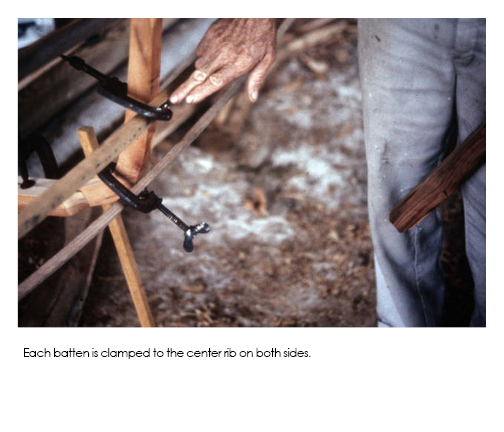

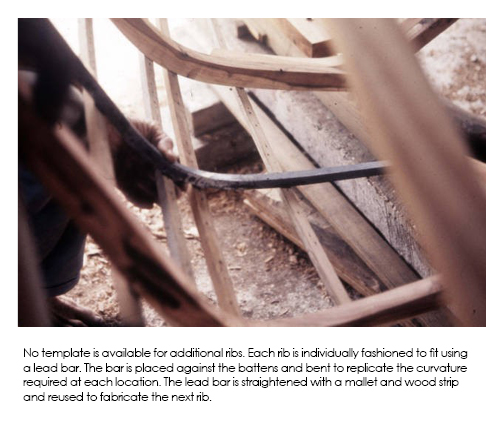

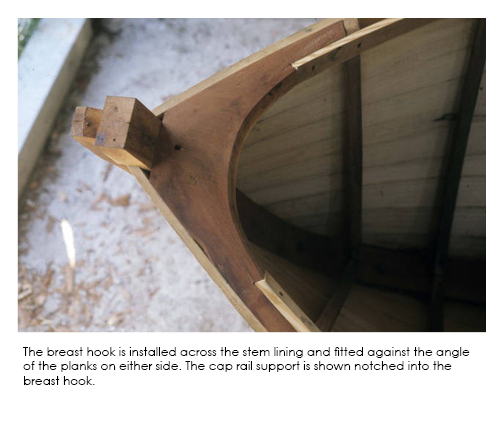

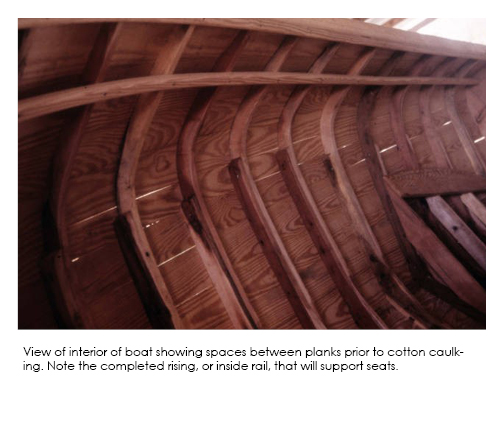

Ribbands, long thin, flexible battens, are temporarily fastened to the boat’s stem and sternpost to ensure each rib (or station frame) is properly shaped to maintain the correct curvature or “sweep” of the hull. On larger boats, double or sister frames were bolted to the first set for added strength.

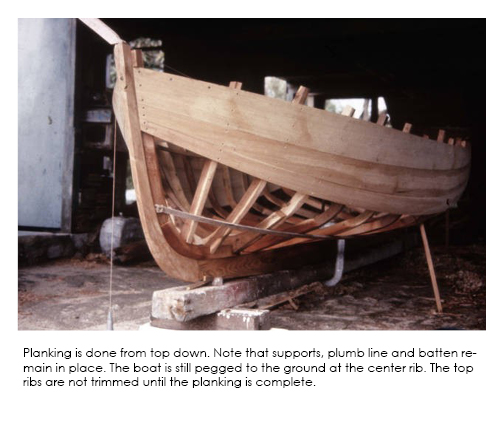

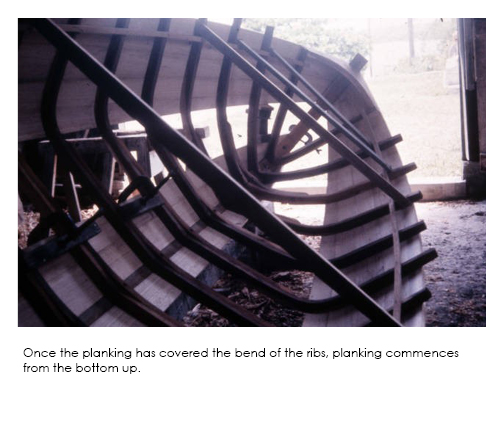

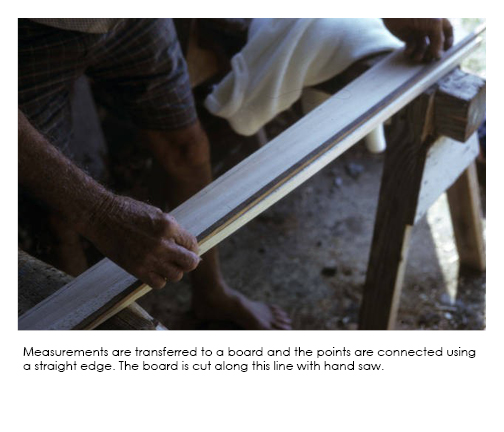

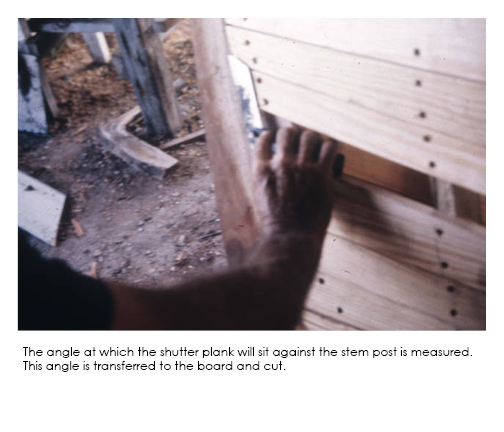

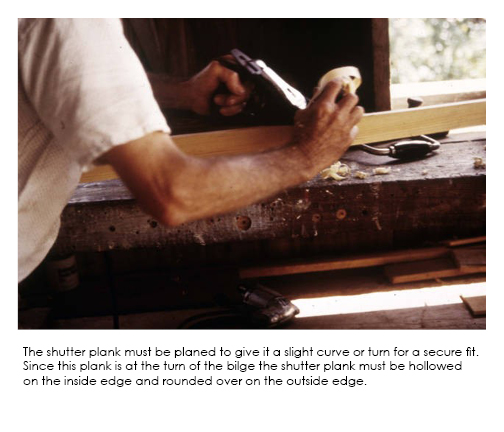

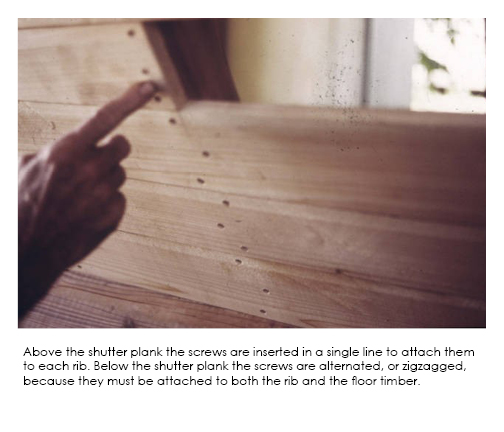

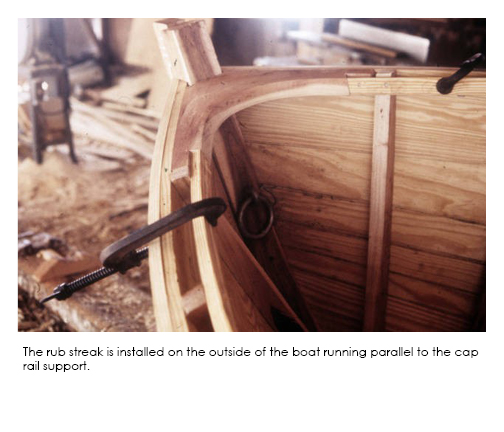

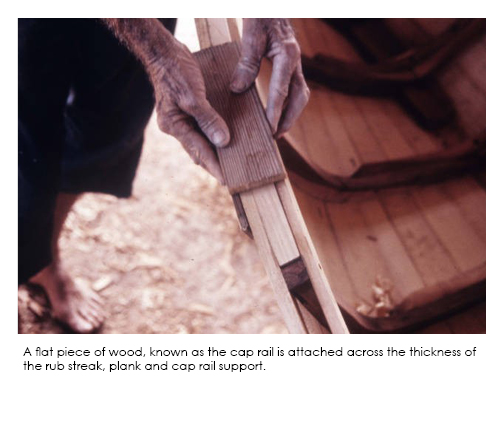

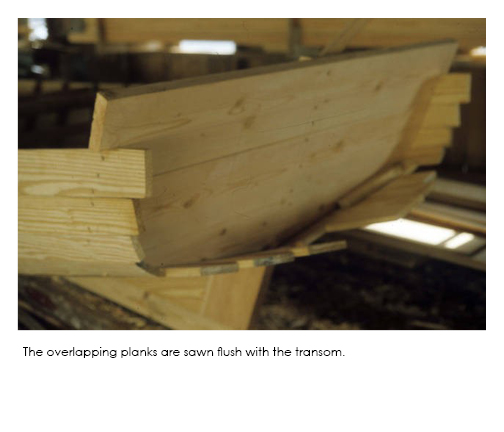

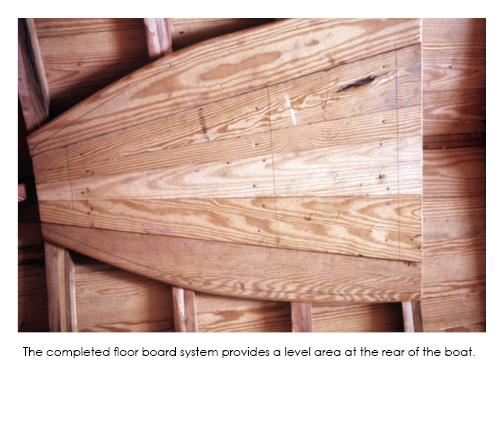

Pine planking, from 1.5-4” thick depending on vessel size, begins with a sheer plank clamped to deck beams. Planking continues both downward and upward. The final plank, the shutter plank, that must be custom shaped to fit into the remaining space.

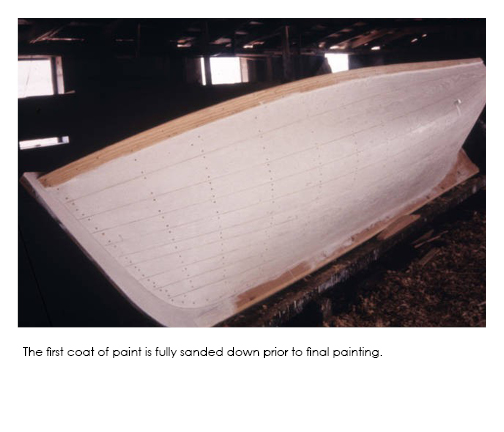

Planking was secured directly to frame stations using hot dipped galvanized iron nails, copper fastenings or wooden pegs that are countersunk and puttied over. Planking was then caulked with strands of cotton, painted and then puttied with white lead mixed with linseed oil. A waterproofing solution of pine tar and pitch was applied over caulking to seal any gaps.

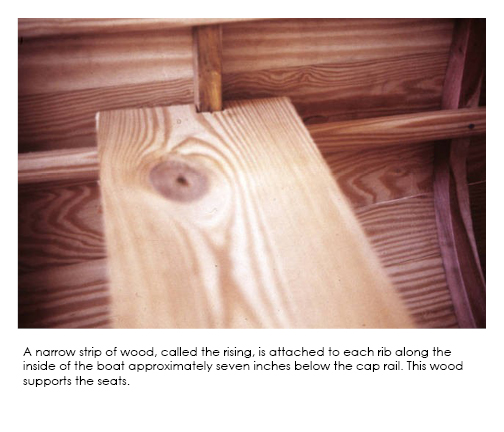

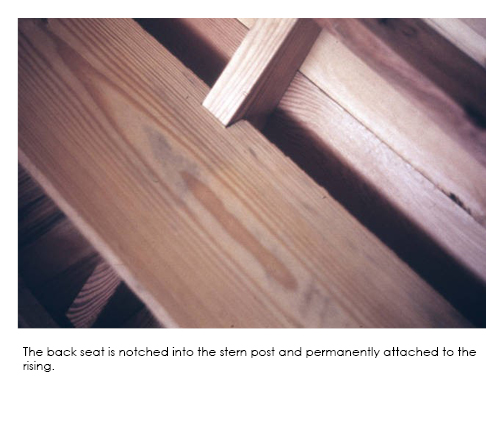

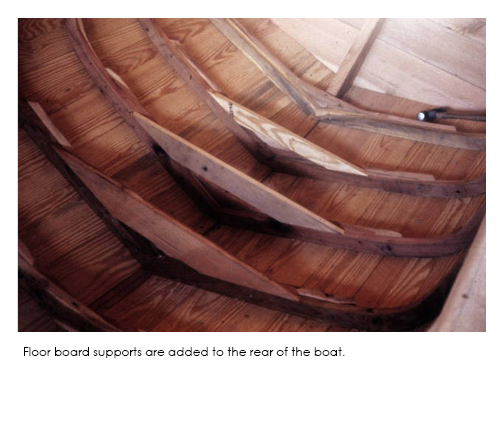

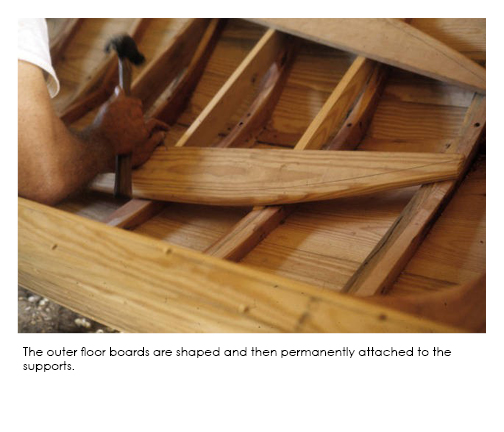

A deck may be added for larger boats, supported by beams and crosspieces. Seats, storage compartments, and structural reinforcements are built inside the hull. Cabins and hatches are built of pine.

The rudder and tiller are hand-shaped, carefully fitted pieces tailored to the boat’s size and purpose. The rudder is a vertical wooden blade, traditionally made from mahogany, pine or cedar, attached to a rudder post mounted on the transom using gudeons or sockets. The rudder is then attached by pintles a type of hinging hardware. These fittings allow the rudder to pivot freely while staying securely in place. A tiller, crafted from a single piece of hardwood, is bolted or mortised to the rudder head. The tiller may be curved or angled to allow clear steering.

Types of Boats

Dinghy

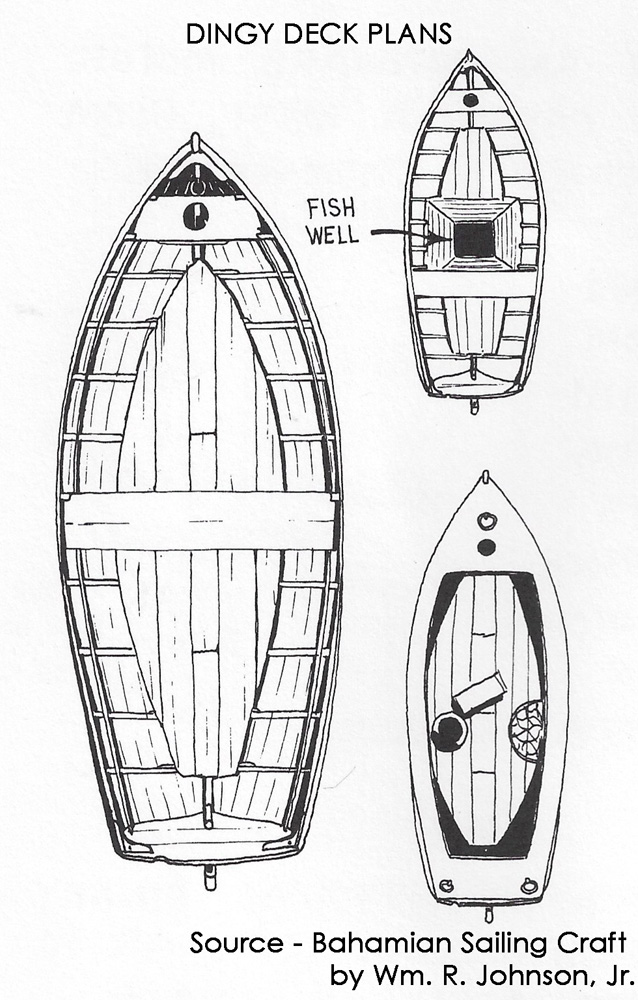

The dinghy is a small boat, nine to eighteen feet long, traditionally used for fishing, cargo, lifeboats, and inter-island transport.

Traditionally, dinghy lines vary by Island. The Abaco dinghy is known for its full transom and smoothly finished construction. The Andros dinghy, more roughly constructed, typically has a convex or moon sheered hull and is known for its speed.

A specialized dinghy has been developed by craftsmen of Savannah Sound, Eleuthera. To accommodate the shallow and shoal conditions of the island, the dinghy is flat bottomed and narrow, allowing them to remain upright when the tidal flats are exposed.

Dinghies can be propelled via outboard motors, but some are rigged with a full mast, boom and sail. Another traditional method of propulsion for dinghies is sculling.

Sloop or Fishing Smack

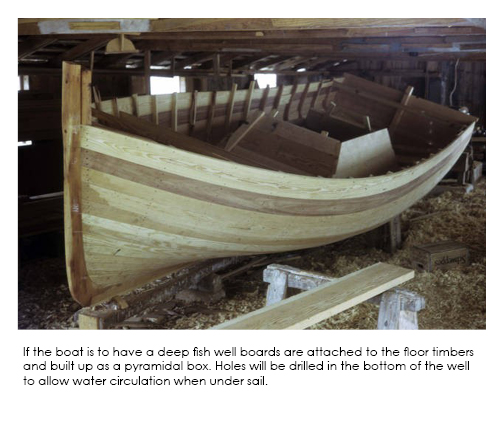

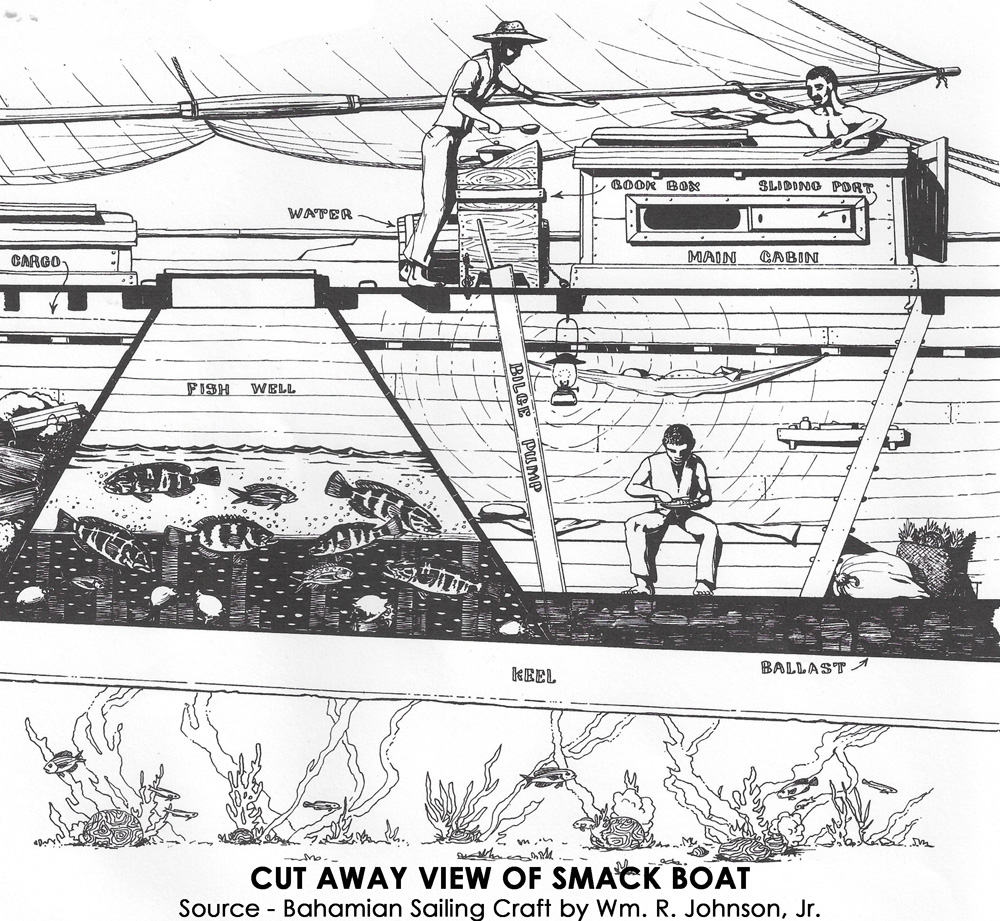

The smack boat or bowsprit sloop, ranging in size from 18’ to 40’, was the most common type of sailboat. Historically designed as a working boat for fishing, the smack has a single mast, mortised into the keel the number of inches behind the foot of the stem as the length of the keel in feet. This boat has a full deck with a cabin accessed by sliding hatch. The fish well, constructed in a pyramid shape, narrowing toward the keel, with holes that allow water circulation when under sail is located mid ship. A galley consisting of a cook box constructed of wood and filled with sand on which a fire can be safely maintained is located on deck. The ship is rigged with a mainsail secured to a wooden headboard. The main sail and jib are handsewn with widths of heavy cloth running parallel to the side edge and laced to the mast.

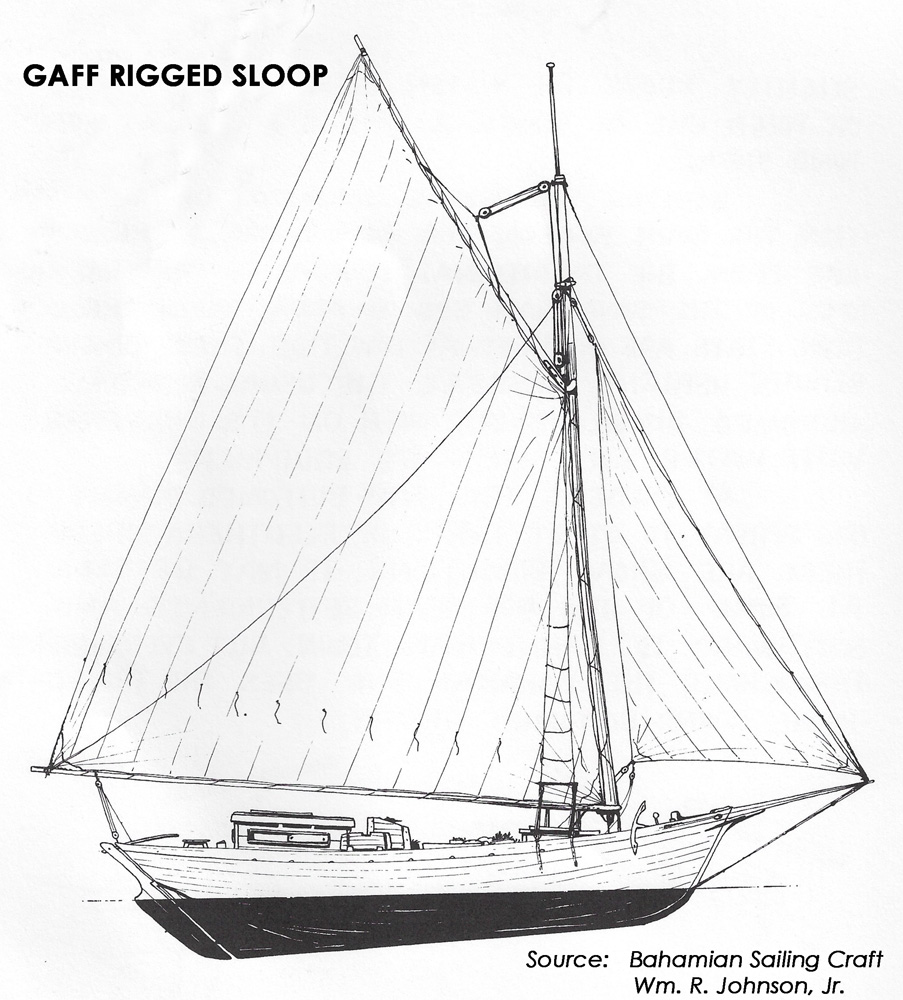

A variation, the gaff-rigged smack boat, was developed in response to varied sea and wind conditions in the southern islands. This boat has a shorter mast and a high peaked gaff mainsail.

Another type of sloop, called a bare-head smack, lacks a bow sprint. Originally developed to transport salt from the Turks and Caicos Islands, they were converted to fishing and cargo hauling trades. The bare-head smack generally has a twenty-three-foot deck length; a low wide transom; greater rise to the bow; and a deeper draft. These styles of boats were built on Andros, Eleuthra and Long Island where the high bow is of benefit in the typical choppy seas.

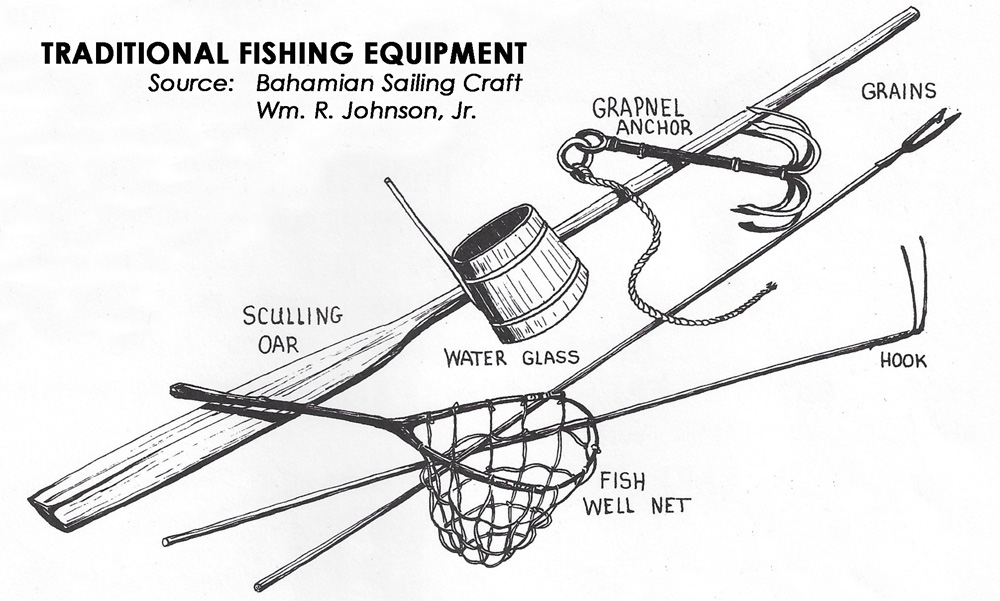

The essential tools found on a typical working boat include a sculling oar, grapnel anchor and lines, , water glass/bucket, machete or hatchet, wooden scoop bailer, water keg, sand bags, scrap irons, rock and an iron tub.

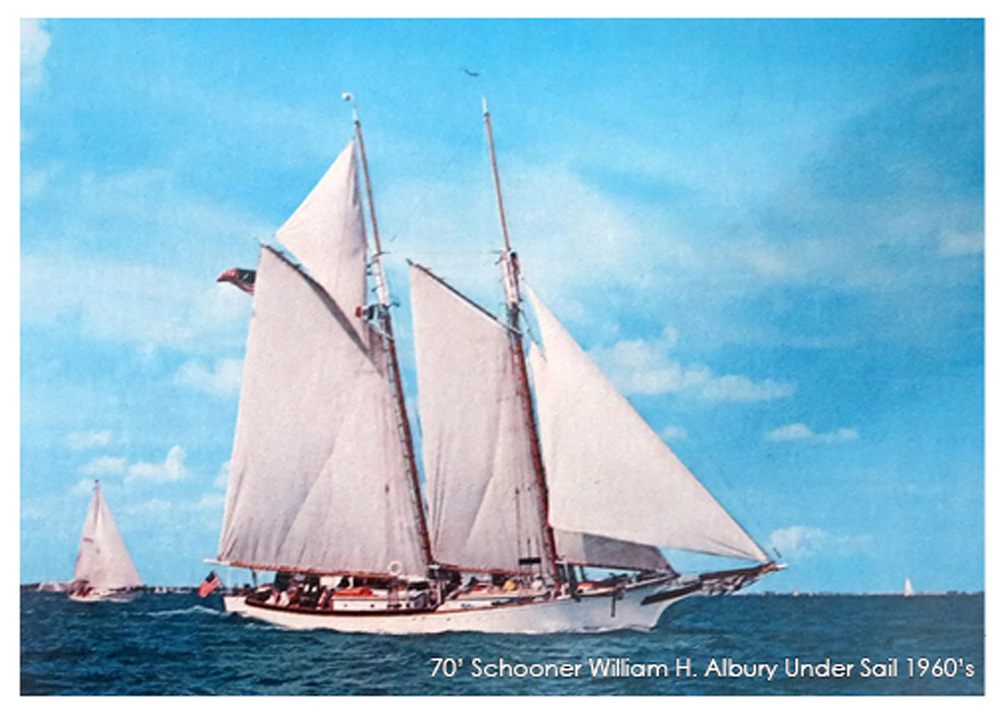

Schooner

Originally built for the sponging trade, schooners were about fifty feet in length (35’ on the keel), had two or more masts, a long bowsprit and were typically gaff-rigged. These vessels had a crew of twenty and carried eight to ten dinghies on deck. These vessels were traditionally built on Abaco, Andros and Harbour Island between 1890 and 1938.

During the sponging era, schooners worked the area of the “Mud” off Andros. The crew, consisting of ten men, usually remained on board for 5-8 weeks. Upon returning to Nassau they sold their cargo to the Greek owned Sponge Exchange.

Schooners, when not engaged in sponging, were used for turtling and cargo. During Prohibition, these vessels were used for intermediate hauling of liquor between Nassau and boats servicing the United States. The 1926 and 1929 hurricanes destroyed many schooners and the failure of the sponging trade in 1938 ended further construction of this type of vessel.

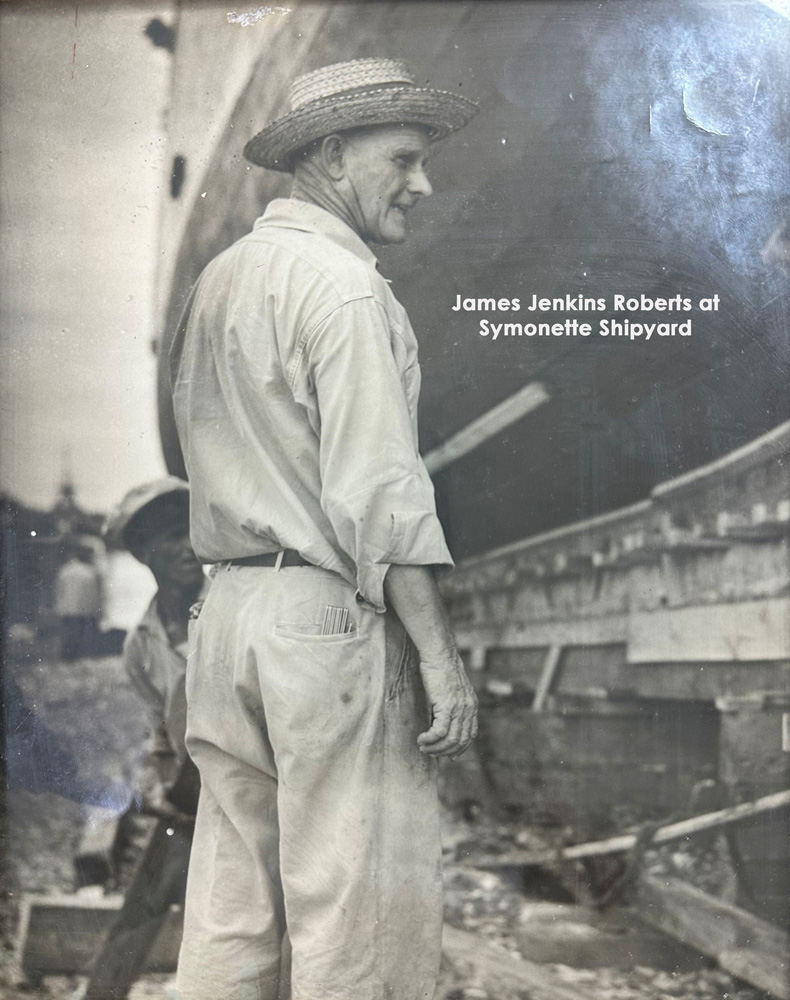

The “Abaco Bahamas”, a three masted schooner, was the largest boat built in the Bahamas. Built in 1922 by Jenkins Roberts at Hope Town, Abaco. This schooner was157' 6" in length, 35' 14" in width with a depth of 12 18". It could carry a cargo of 500,000 feet of lumber or a similar cargo of 500 tons. It worked in the lumber trade and for transport of pineapple to Baltimore and Philadelphia.

Traditional Methods of Propulsion

Bahamian boats - especially sloops, dinghies, and mailboats—were designed for versatility and adapted to the region’s shallow banks, open seas, and trade winds. The methods of propulsion reflected the environment, purpose, and resources available.

Sail

Sail was the primary form of propulsion and were historically hand-stitched using canvas, a heavy-duty cotton fabric, treated with linseed oil or tar to improve water resistance.

Bermuda Rig

The Bermuda rig consists of a large, triangular main sail and is used on smaller dinghies and modern racing sloops. The main sail is hoisted on a mast and controlled using sheets and halyards. A smaller triangular sail, known as a jib, can be set forward of the mast, improving balance and handling. A large, balloon-like sail, known as a spinnaker, can also be used in downwind conditions for increased speed.

This type of rig is simple with fewer fittings. It allows a vessel to be sailed “closer to the wind”, making it excellent for racing or heavy weather. With fewer sails and rigging to handle, it’s easier for one or two sailors to manage.

Gaff Rig

Gaff rig sails are common on schooners, ketches, and Bahamian sloops. A gaff-rigged sail is a four-sided sail that is supported at its top edge by a headboard called a gaff. This type of rig spreads more canvas for a given mast height as the gaff supports the upper part of the sail. Because the weight of the sail is spread lower along the mast it gives the vessel better balance and stability in rough seas. The sail can be partially lowered, or reefed, in sections for easier handling. The larger, lower sail area is powerful in light winds making it useful for vessels sailing in variable Caribbeans winds.

The Process: From Chalk Line to Sail

Traditionally sails are cut laid out on the floor of a boat shed or even a backyard slab of concrete. Sailmakers mark out the curves using chalk, measuring tapes, and string. Working without plans the sailmaker’s crafts every curve, crease to the boat’s design and anticipates how the vessel handles under different wind conditions. The panels are shaped with subtle curves, called broadseaming, to create the right draft—a belly that gives the sail its power. This shaping is critical. If the sail is too flat, it won’t pull - too deep, and it becomes hard to control.

Panels are stitched together by hand or using industrial sewing machines. Seams are reinforced with double stitching, and patches of canvas or leather are added at high-stress points like the corners.

Grommets, metal or rope-reinforced eyelets added for attaching the sail to rigging lines, are punched in by hand. Ropes are sewn into hems (called boltropes), which help the sail hold its shape. Reef points may be added for shortening the sail in strong wind. Every detail—from the type of thread to the angle of the seams—affects performance.

Sculling

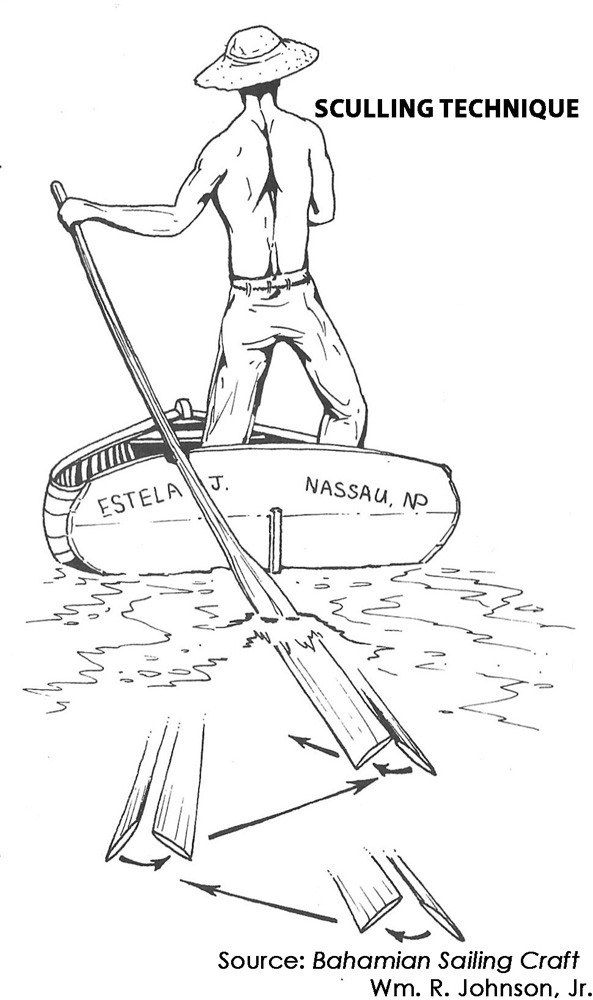

Sculling, a technique unique to the Bahamas, is a traditional means of propelling a boat with the use of a single long oar typically made from pine. This method of propulsion is practical for shallow waters, calm weather and is efficient for short distances.

The sculler stands at the center back of the boat facing forward. The oar is balanced in a notch located on the port transom or left rear of the boat. With the right leg forward the oar is held in the left hand. The sculler works the oar side to side through the water, at right angle to the keel, or length, of the boat. By alternately pushing and pulling, with a slight flip of the wrist at the change of direction, a rhythmic motion is established to move the boat forward. The right hand can be used during the pull portion of the stroke for additional leverage. This method allows the dingy to be propelled through the water with significant power, but with little effort once the rhythmic motion is established.

Conclusion

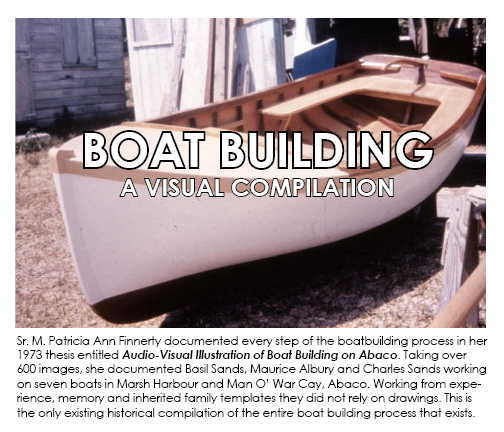

Boatbuilding in the Bahamas is more than just a craft—it is a testament to the resourcefulness, artistry, and maritime spirit of the Bahamian people. From the hands of master boatwrights in Abaco to the vibrant regattas that keep the tradition alive, these wooden vessels remain an enduring symbol of Bahamian identity. See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZBKj8c73gKQ&t=722s for a historical complete documentation of boat building in the Bahamas

Boat Builders of the Past

James Jenkins Roberts (1886-1973)

James Jenkins Roberts designed and built the largest 3 masted schooner, the “Abaco-Bahamas”, in the Bahamas at Hope Town, Abaco in 1921. In 1924 he became the manager of Symonette's Shipyards. By 1939 the shipyards were the largest south of Jacksonville and in all the Caribbean. During this period Jenkins Roberts built 2 wooden mine sweepers for the British Admiralty and designed and built several 120’ cargo ships that were used in inter Island trade and also as cargo ships running to Caribbean Ports. He designed and built the “William Sayle”, “Ann Bonney", “Caribbean Queen" and "Jenkins Roberts".

Roland T. Symonette (1898 – 1980, New Providence)

Roland Symonette built a small boat yard at Hog Island to build large boats to enter the blockade running trade. There the “Jenkins Roberts” and “Richard Campbell” were built. In 1938 the shipyard was relocated to East Bay Street. It was renamed the Nassau Shipyard in 1960.

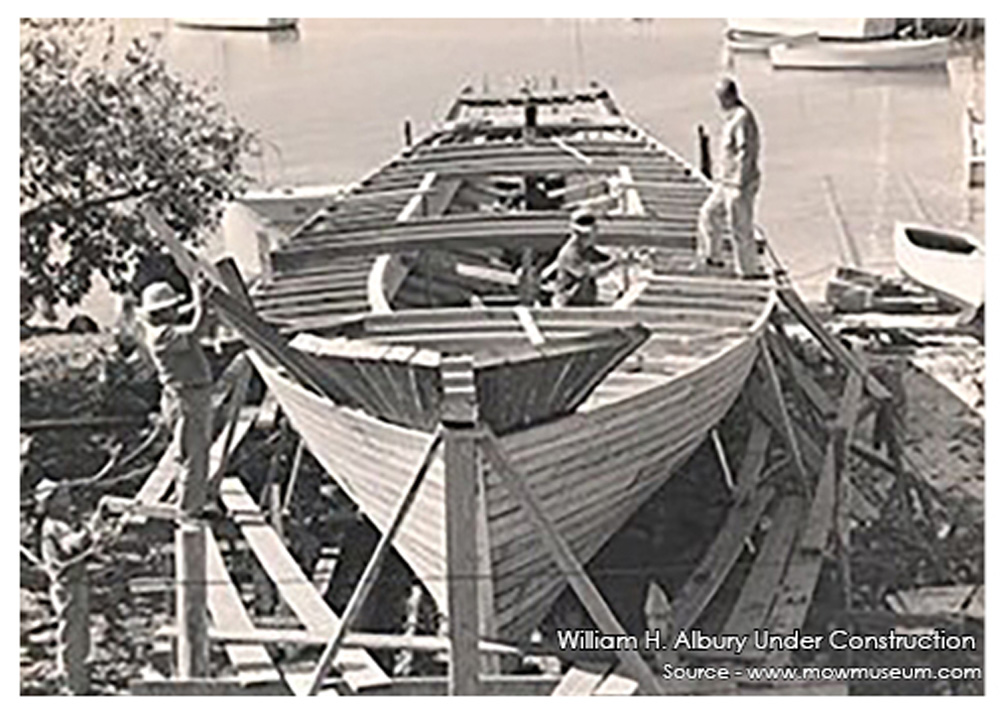

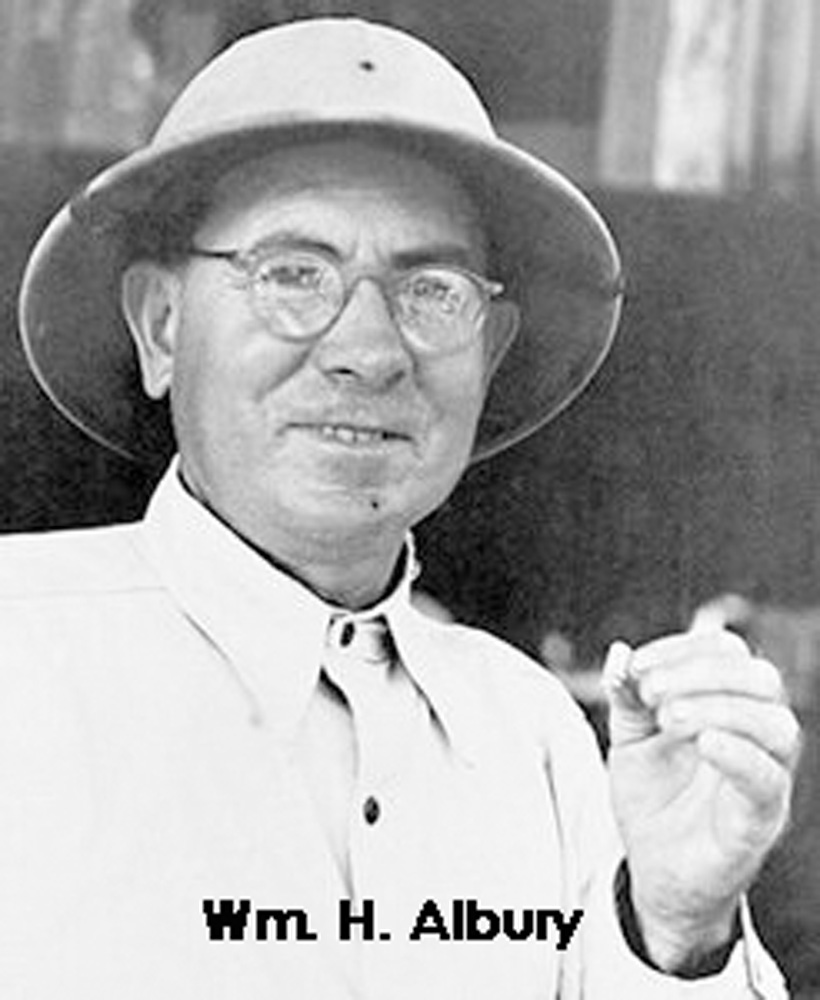

William H. “Uncle Will” Albury (1899–1987, Man-O-War Cay, Abaco)

Considered one of the greatest Bahamian boatbuilders of the 20th century. He built the “Joyce Roberts” and the “Donald Roberts” that were used to haul lumber from the lumber camp at Pine Ridge, Grand Bahama to Cuba and Jamaica in the 1930’s. He also built the famous schooner “Equinox” and many other wooden sloops used for trade and racing.

Maurice Albury (1908 - 1977, Man-O-War Cay, Abaco)

Maurice Albury was a respected Bahamian boatbuilder from Man-O-War Cay, Abaco, a community renowned for its long tradition of wooden boat construction.

Ernest "Ernie" Pinder (Spanish Wells, Eleuthera)

A master builder from Spanish Wells, known for constructing fishing vessels used by Bahamian spongers and lobster fishermen. Helped transition traditional wooden boats into modern fiberglass designs.

Rupert Knowles (Long Island)

Rupert Knowles was a respected boatbuilder from Long Island who specialized in crafting traditional Bahamian sloops used for both fishing and regatta racing. His designs were known for their speed and durability, influencing modern racing sloops.

Hartley Rolle (Exuma)

Hartley Rolle was known for constructing fast regatta boats, Rolle played a key role in Bahamian sloop racing history. His handcrafted boats won numerous Family Island Regatta championships.

Malvin Roberts (Harbour Island)

Built small, high-performance racing sloops that became well-known in Bahamian regattas. His expertise in sail design and boat balance made him one of the top builders for competitive sailing.

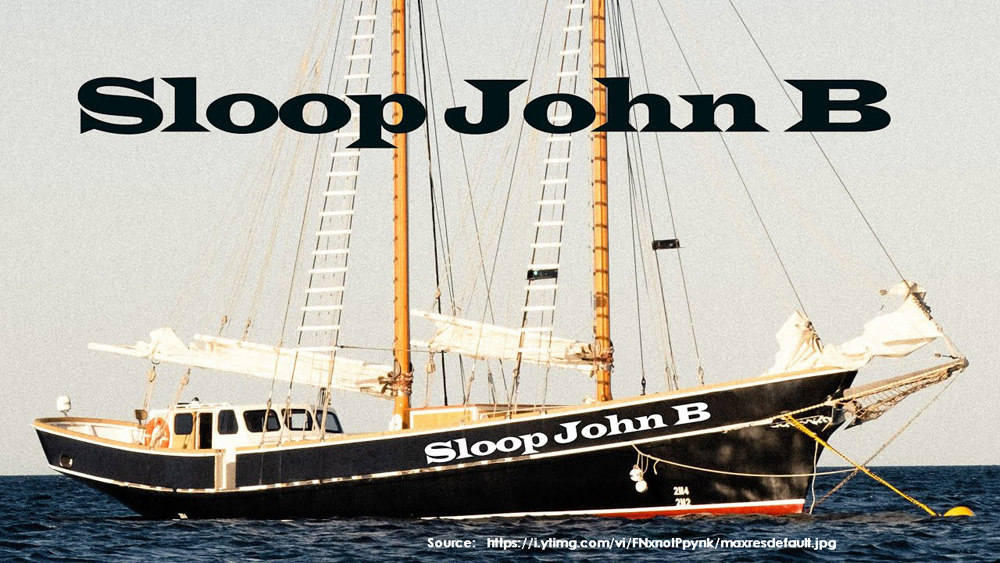

Ship Immortalized in Song

"The John B. Sails" is a Bahamian folk song from the early 1900s. It tells the story of a sailing trip gone wrong aboard a sponging schooner called the “John B”. Named for John Bethel, the lyrics describe a chaotic and miserable voyage, with the singer pleading to go home: “I want to go home / Let me go home / I feel so broke up, I want to go home.”

The song was first published in 1916 in Harper's Monthly Magazine and later in Carl Sandburg’s 1927 collection "The American Songbag", which helped preserve and spread American folk songs.

In the early 1960s, Al Jardine, a member of The Beach Boys, introduced the song to the band. Brian Wilson arranged and produced the Beach Boys’ version, adding rich harmonies and orchestration. It was released in 1966 on their iconic album "Pet Sounds".

Sailing Lore

Thunderbolt or Thunderstone

A Thunderbolt or Thunderstone is a smooth hard stone about three inches long. They are considered good luck and protection against being struck by lightening at sea. Lore tells that these stones come to the surface of the earth fourteen years after a lightning strike. Another version claims that they have fallen from the sky.

Cutting Waterspouts

Lore from the southern islands claims that if the tail of a waterspout, also known as a devil’s tail, is symbolically cut by a knife it will withdraw back into the clouds.

Old Saying

When a boat is launched, the waters of the world rise ever so slightly.